When Life Insurance Is Sold, Not Bought

They say life insurance is a product that's sold, not bought. This decades-old maxim was shamefully brought to light when the Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario (FSRA) looked into troubling sales practices in the life insurance industry.

Troubling, indeed. FSRA examined life insurance agents at three firms – World Financial Group, Greatway Financial Inc., and Experior Financial Inc. – and found the agents broke about 184 rules under the insurance act (that's all?).

FSRA looked at 24 client files from these agents and found that a Universal Life (UL) insurance product was sold in the majority of cases, despite there being no specific life insurance need:

- In 33% of cases, the customer was sold overfunded UL with the expressed or implicit purpose of helping to fund retirement or grow the value of the client’s estate, yet in 75% of those cases the client did not appear to have a TFSA or RRSP.

- In all these instances the client was a single person in their 20s or early 30s, with no dependents and only modest income.

- In fact, in 70% of the instances the insured stated an annual income of $60,000 or less.

- Further, in 83% of the files reviewed there was no indication that the client had any TFSA or RRSP, and in almost 30% of the cases the client was carrying high interest personal debt, which was not factored into the recommendations.

Also caught in FSRA's crosshairs was the multi-tiered (pyramid shaped?) business recruitment model prevalent at these firms:

“When compensation for life agents is heavily influenced by the sales of individuals they recruit, this creates the potential to focus on recruiting to greater extent than agent suitability and customer needs analysis.”

FSRA took enforcement action against 65 life insurance agents, and says it may conduct further reviews and follow up with insurers. Good.

Life insurance agents may target those with poor financial literacy skills. The FSRA review showed that permanent insurance is often mis-sold to unsuspecting customers who may not have a need for insurance (let alone life-long insurance), and who may not fully understand the complex product.

For those interested, the team at PWL Capital put together a white paper explaining the ins and outs of permanent insurance that's well worth the read. They suggest that the motivations to sell insurance as an investment are, in many cases, related to conflicts of interest.

“It is common for insurance agents to earn a commission of 50% to more than 100% of the first year’s policy premium. For large policies, the financial incentive for agents to recommend permanent insurance is substantial.

Importantly, commissions are typically paid to the agent upfront at the time of sale, and that commission only has to be repaid if the policy is cancelled within a two-year window. The agent has minimal financial incentive to provide longterm service and advice to the policyholder, which is starkly misaligned with the fact that many policies are intended as solutions for which the benefit will not be realized for many decades to come.

There is little accountability for an agent who sold an unsuitable permanent policy 10, 20 or 30 years ago.”

The PWL team also questioned the need for permanent insurance, using a common example of a family cottage that is intended to stay in the family. The idea being to take out a permanent insurance policy to cover any capital gains so that the children can keep the cottage as intended.

While permanent insurance can be used to cover this tax bill, it may not be the best tool. Permanent insurance is expensive.

“A Term-to-100 life insurance policy with a $250,000 death benefit for a 40-year-old healthy male costs about $2,500 per year. If Mom and Dad had simply instead invested their $2,500 annual premiums into low-cost index funds, the resulting investment could likely cover the cottage’s expected tax liability and more. For an investment with contributions identical to the insurance premiums at $2,500 per year until age 90, the required net of tax return to match the death benefit is only 2.6%.”

Were you sold an inappropriate insurance policy?

Financially savvy consumers know that term insurance is cheaper and more plentiful (i.e. you can get more coverage) than permanent insurance. They also know that insurance is insurance – a transfer of risk – and should not be combined with their investments, especially when the alternative is to invest in low cost index funds.

That's why the phrase “buy term and invest the difference” was coined.

Indeed, the PWL team concluded that a lower level of permanent coverage should never be put in place at the expense of a higher level of required term coverage.

But what if you're just hearing about this now, and you realize you were sold a permanent insurance policy that is not in your best interest?

I reached out to Jaclyn Cecereu, a financial planner at PWL and co-author of the white paper above, to ask about this exact situation.

She agreed that many people are sold a permanent policy before realizing it may not be ideal for their needs.

When a policyholder owns permanent insurance that isn't actually necessary for them to have, the cost/benefit of cancelling or unwinding has to be known.

- Cost = what are you giving up if you cancel?

- Benefit = what are you saving if you cancel?

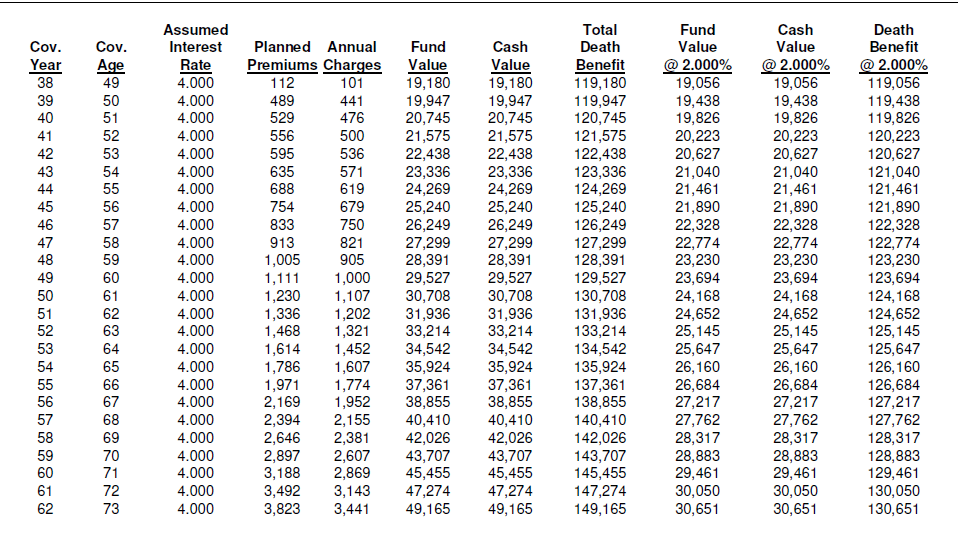

“To do this we look ahead and ignore all past premiums made (i.e. sunk costs are not considered). We review the policyholder’s latest in force illustration to determine whether the policy would be worth buying today assuming there were no coverage in place. The illustration can be requested from the insurance advisor, or directly from the insurance company if there is a desire for discretion. It will include up to date projections of the premium schedule, cost of insurance, cash value, death benefit, dividend scale, etc.”

Ms. Cecereu uses this to figure out the assumed internal rate of return, or in other words, the effective annual after-tax rate of return required on another investment to match the insurance. This is useful to compare existing coverage with other alternatives, in particular the possibility of getting term insurance and investing the difference in planned premiums.

“You are better off with term if, given the outlook today, investing the net premium savings offers better performance than keeping the permanent policy.”

In the early years of owning a permanent policy there is little to no build up of cash value (i.e. equity), so the policyholder might walk away with nothing in return for their initial premiums made. Sort of like paying the mortgage, property tax, and maintenance costs on a home that has not appreciated in value.

Behaviourally, there is an endowment effect bias at play here too which makes it really difficult to walk away. But, it softens the blow to compare sunk costs to the long-term prospect of continuing to incur high unnecessary premiums and potentially giving up higher investment returns.

Some policies have early surrender charges that expire years after a policy is put in force, and these need to be considered too. Instead of cancelling outright, a cash surrender value might buy the policyholder a few years of premium offset. The decision to cancel could be deferred until that cash value runs out, and in the meantime a new term policy can be put in place.

“It is worth noting that if the term insurance application came back rated or denied, you would keep the permanent policy after all.”

Ms. Cecereu goes on to explain that there are situations in which permanent insurance makes more sense than term. This might come up if there is a family cottage with a large, embedded capital gain, where the family wants to guarantee the cottage is inherited by the next generation. Permanent insurance can be used as a tool to cover the eventual tax liability on that transfer. This avoids otherwise having to sell the asset to pay the taxes owing on death.

“We often see it used as a way to mitigate known tax liabilities on death; the date or timeline of the insurance need is unknown, but the amount of the insurance need is (somewhat) known.”

She says they also see permanent insurance used as a way to access cash during the insured’s lifetime, particularly if most other assets are more illiquid, e.g. real estate or private investments.

This is more popular with corporately-owned policies and is often sold as a way to avoid income tax. You can borrow against the overfunded portion of a permanent policy (although this is done at a high unsecured debt rate) to help with liquidity needs.

“In most cases though, there are more efficient avenues to access liquidity, i.e. drawing on an investment portfolio or even borrowing against real assets.”

Final Thoughts

I found myself in a fit of rage reading the FSRA reports on observed practices in the sale of Universal Life insurance. There's clear harm being done to financial consumers from poorly trained, commission-hungry agents and their (lack of) supervisors.

Term insurance is more appropriate for the vast majority of financial consumers. Don't even consider Universal Life insurance unless:

- You have a genuine need/purpose for permanent insurance

- You are already maximizing other tax advantaged accounts, such as TFSAs (and/or RRSPs or Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs) as applicable) and you do not need access to your overfunded premiums in the short-to-medium term

- You are prepared to carefully monitor and adjust your policy on an ongoing basis

- You have sufficient means to support increased premiums in the case of future poor investment performance or volatility

Understand that permanent insurance sales are heavily influenced by commissions, and there's a literal army of life insurance agents out there trying to sell you this stuff (World Financial Group has nearly 11,000 agents in Ontario alone).

Finally, if you have been sold an inappropriate permanent insurance policy, it's worth looking into the details to see if it makes sense to walk away from the policy in favour of more appropriate term insurance. Understand the trade-offs, though. How much is the cash value? What are the surrender charges?

And, don't cancel the permanent policy without having term policy in place.

Great article!

Would it make any sense for a 70 year old couple to buy last to die universal life insurance to cover the capital gains tax on a cottage? My math says that one would have to pay premiums for 40 years to cover the ultimate payout on the policy. Doubtful that either would still be alive in 40 years. Are premium rates fixed for the life of the policy or do they increase with age? That could be a game changer.

Jaclyn Cecereu replying here. UL would not be ideal, but a T-100 is worth exploring, as well term products like a T-30.

I’ve seen this pitch many, many times before, and it just doesn’t make sense to me [at least, logically; it’s a good sales pitch because it’s a problem many have run into recently and so resonates emotionally]. It’s a case where permanent insurance is a better (less bad) fit than term, but a problem that is not well-solved by insurance in the first place.

The problem is that insurance is nominal, and (unless you’re unlucky) the amount is chosen long in advance, while the real estate market can be (and was!) highly unpredictable over those timescales. An example to illustrate what I mean:

Imagine in 2000, my 50-year-old dad decided to take out a policy to cover the risk of big capital gains on the cottage. He bought the cottage for $270k, and in 2000 it had appreciated roughly zero dollars from that point, so it seems like a silly risk to think about insuring. But, figuring it might appreciate and wanting to be extra cautious: how much insurance does he need? Even taking a reasonable assumption (for the time) that it will appreciate 3%/yr doesn’t help get a policy size. If he lives to 75, the surprise capital gains tax might be $75k, but if he lives to 95 it might be $180k. What do you get a policy for? How do you insure against a liability that grows over time?

Say he aims for $100k, the tax bill he expects if he lives to 80 years old — maybe a backup plan could be to borrow against the policy at 80 and transfer the place then if he’s still kicking.

Well, as luck would have it, dad died of cancer in 2020, just as the rural Ontario real estate market went absolutely bonkers from rock-bottom rates and the exodus from the city. The cottage appraised for a whopping $1.4M, and so $282k in tax is now due to keep the cottage in the family. But even with all that foresight to get insurance, the policy barely covers a third of the actual hit. And you would have had to have been insane to take out enough insurance at the time to actually cover the appreciation we saw in such a short period of time — you’d be insuring more than the place was worth at the time!

So the premise is to “guarantee” the cottage (or Vancouver special, or other rapidly appreciating property) is inherited by the next generation, but you can’t insure against that specific risk [note to insurance companies: this is product a niche group of people want to buy if you want to invent it], you can only take out a certain dollar value that will hopefully be enough to cover eventual capital gains tax. And if the real estate market is hot enough, which is the situation recently and what makes people want to insure against that risk, it’s almost impossible that the people involved would have taken out enough insurance far enough in advance (because almost nobody foresees in advance how hot the market might be to take out a sufficiently large policy, or if they do foresee it sounds crazy — taking out a policy for more than the cottage is even worth at the time to pay for future capital gains tax). The problem is opposite that of most life insurance needs — the need grows over time rather than remaining the same or shrinking.

I agree with you entirely. Permanent insurance CAN be used to cover this tax liability, but it may not be the best tool. We wrote about this situation specifically in our white paper:

“Permanent insurance is expensive. A T100 life insurance policy with a $250,000 death benefit for a 40-year-old healthy male costs about $2,500 per year. If Mom and Dad had simply instead invested their $2,500 annual premiums into low-cost index funds, the resulting investment could likely cover the cottage’s expected tax liability and more. For an investment with contributions identical to the insurance premiums at $2,500 per year until age 90, the required net of tax return to match the death benefit is only 2.6%. To be fair to the case for permanent insurance, Mom and Dad may not want only a good chance at covering the tax liability; if they want to guarantee a specific amount payable tax-free at death, permanent

insurance is uniquely positioned to deliver that from the joint perspective of certainty and tax efficiency. Additionally, life insurance death benefits assigned to named beneficiaries bypass probate, result in near immediate liquidity, and are much more difficult to contest than assets left in a will.”

https://www.pwlcapital.com/resources/permanent-life-insurance/

Great read, Thanks Rob. It’s unfortunate how often this happens.