An Evidence Based Investing Guide

In a world full of conflicts of interest and questionable information, I'd like to offer this evidence based investing guide to help you make informed choices with your money.

What’s the point of investing, anyway? We invest our money for future consumption, with the idea that we’ll earn a higher rate of return from investing in a portfolio of stocks and bonds than we will from holding cash.

But where does this equity premium come from? And how do we capture it without taking on more risk than is needed? Moreover, how do we control our natural instincts of fear, greed, and regret so that we can stay invested long enough to achieve our expected rate of return?

For decades, regular investors have put their trust in the expertise of stockbrokers and advisors to build a portfolio of stocks and bonds. In the 1990s, mutual funds became the investment vehicle of choice to build a portfolio. Both of these approaches were expensive and relied on active management to select investments and time the market.

At the same time, a growing body of evidence suggested that stock markets were largely efficient, with all of the known information for stocks already reflected in their prices. Since markets collect the knowledge of all investors around the world, it’s difficult for any one investor to have an advantage over the rest.

The evidence also showed how risk and return are intertwined. In most cases, the greater the risk, the higher the reward (over the long-term). This is the essence of the equity-risk premium – the excess return earned from investing in stocks over a “risk-free” rate (treasury bills).

Evidence-based investing also highlights the benefit of diversification. Since it’s nearly impossible to predict which asset class will outperform in the short-term, investors should diversify across all asset classes and regions to reduce risk and increase long-term returns.

As low-cost investing alternatives emerged, such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that passively track the market, the evidence shows that fees play a significant role in determining future outcomes. Further evidence shows that fees are the best predictor of future returns, with the lowest fees leading to the highest returns over the long term.

Finally, it’s impossible to correctly and consistently predict the short-term ups and downs of the market. Stock markets can be volatile in the short term but have a long history of increasing in value over time. The evidence shows staying invested, even during market downturns, leads to the best long-term investment outcomes.

Evidence Based Guide To Investing

So, what factors impact successful investing outcomes? This evidence based investing guide will reinforce the concepts discussed above, while addressing the real-life burning questions that investors face throughout their investing journey.

Questions like, should you passively accept market returns or take a more active role with your investments, should you invest a lump sum immediately or dollar cost average over time, should you invest when markets are at all-time highs, should you use leverage to invest, and how much home country bias is enough?

To answer these questions, I looked at the latest research on investing and what variables or factors can impact successful outcomes. Here’s what I found.

Passive vs. Active Investing

The thought of investing often evokes images of the world’s greatest investors, such as Warren Buffett, Benjamin Graham, Peter Lynch, and Ray Dalio – skilled money managers who used their expertise to beat the stock market and make themselves and their clients extraordinarily wealthy.

But one man who arguably did more for regular investors than anyone else is the late Jack Bogle, who founded the Vanguard Group. He pioneered the first index fund, and championed low-cost passive investing decades before it became mainstream.

Jack Bogle’s investing philosophy was to capture market returns by investing in low-cost, broadly diversified, passively-managed index funds.

“Passive investing” is based on the efficient market hypothesis – that share prices reflect all known information. Stocks always trade at their fair market value, making it difficult for any one investor to gain an edge over the collective market.

Passive investors accept this theory and attempt to capture the returns of all stocks by owning them “passively” through an index-tracking mutual fund or ETF. This approach avoids trying to pick winning stocks, and instead owns the market as a whole in order to collect the equity risk premium.

The equity risk premium explains how investors are rewarded for taking on higher risk. More specifically, it’s the difference between the expected returns earned by investors when they invest in the stock market over an investment with zero risk, like government bonds.

Bogle’s first index fund – the Vanguard 500 – was founded in 1976. At the time, Bogle was almost laughed out of business, but nearly 50 years later, Vanguard is one of the largest and most respected investment firms in the world. Who’s laughing now?

In contrast, opponents of the efficient market hypothesis believe it is possible to beat the market and that share prices are not always representative of their fair market value. Active investors believe they can exploit these price anomalies, which can be observed when trends or momentum send certain stocks well above or below their fundamental value. Think of the tech bubble in the late 1990s when obscure internet stocks soared in value, or the 2008 great financial crisis when bank stocks got obliterated.

Comparing passive vs. active investing

Spoiler alert: there is considerable academic and empirical evidence spanning 70 years to support the theory that passive investing outperforms active investing.

The origins of passive investing dates back to the 1950s when economist Harry Markowitz developed Modern Portfolio Theory. Markowitz argued that it’s possible for investors to design a portfolio that maximizes returns by taking an optimal amount of risk. By holding many securities and asset classes, investors could diversify away any risk associated with individual securities. Modern Portfolio Theory first introduced the concept of risk-adjusted returns.

In the 1960s, Eugene Fama developed the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which argued that investors cannot beat the market over the long run because stock prices reflect all available information, and no one has a competitive information advantage.

The 1970s gave us Burton Malkiel’s Random Walk Down Wall Street, which argued that historical prices have no predictive power and that investors are better off buying and holding a diversified portfolio rather than trying to beat the market by picking stocks.

And, of course, Jack Bogle launched the first index fund in 1976. The father of passive investing started an index investing revolution that culminated in 2019, when assets invested in U.S. index funds topped those invested in active funds for the first time.

Read: Trillions – How a Band of Wall Street Renegades Invented the Index Fund and Changed Finance Forever

For the past 15 years, the SPIVA scorecard has tracked how well active fund managers around the world perform relative to their benchmark. The results for the active fund industry are damning.

In the United States, 63.17% of large-cap mutual funds underperformed the S&P 500 over a one-year period. Over a five-year period, the number of funds that failed to beat the S&P 500 rose to 77.97%.

In Canada, the results are even more depressing for active funds. Over a one-year period, 88.37% of Canadian equity funds underperformed the S&P/TSX Composite index. That number rose to 97.14% over a five-year period.

Active investors may argue that even though the odds of beating the market are not favourable, it is indeed possible for active funds to beat the market.

The challenge is identifying this outperformance in advance so that you can capture the market beating returns. It’s possible that if you tossed a coin 10 times it could land on heads 10 times in a row. But the odds are overwhelmingly stacked against you. Why would you invest in an active fund knowing that you only have a 2.86% chance of beating the market over a five-year period?

Finally, a significant difference between passive and active investing can be explained by costs. Active funds cost more than passive funds. That’s because active funds need to pay a fund manager and research team. Active funds have higher turnover and pay more transaction costs.

This idea is highlighted in William Sharpe’s 1991 paper, The Arithmetic of Active Management.

If “active” and “passive” management styles are defined in sensible ways, it must be the case that:

- Before costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will equal the return on the average passively managed dollar and;

- After costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will be less than the return on the average passively managed dollar.

These assertions will hold for any time period. Moreover, they depend only on the laws of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Nothing else is required.

The Verdict

Investing has been solved. A risk-appropriate portfolio of low cost, globally diversified, index funds or ETFs is the best and most reliable way to achieve long-term investment returns. While active investing can outperform the market over shorter periods of time, it is near impossible to do with any long-term consistency and reliability.

Lump Sum Investing versus Dollar Cost Averaging

Investors face countless difficult decisions along their investing journey. One of those decisions involves how best to invest a large sum of money, like the proceeds from the sale of a house, a business, or from a bonus or inheritance.

The choice often comes down to timing, and whether to invest the lump sum of money all at once, invest portions of it over time, or wait for an opportune time such as a market crash, or after a significant event such as a major election.

Behavioural issues abound. First, it doesn’t always feel like a good time to invest. Stocks may be falling due to an economic downturn. No one wants to “catch a falling knife” and so investors would prefer to wait for markets to stabilize before investing. On the other hand, stock prices may be high thanks to a strong economy and exuberant investors. In this case, it feels risky to invest when stocks could potentially crash at any moment.

We also tend to treat windfalls differently than we treat other money, say from a regular paycheque. Funds received through an inheritance might be invested more conservatively than money won in a lottery. This type of mental accounting could impact the decision to invest a lump sum at once or in smaller pieces over time.

When investors are faced with a choice between lump sum investing or dollar cost averaging over time, there is a mathematical answer and a behavioural answer. This section explores both of these solutions.

The Mathematical Answer

The math says when you have a sum of money, it’s best to invest the entire amount immediately. Vanguard studied this in a 2012 paper titled, Dollar-cost averaging just means taking risk later, and found that immediate lump sum investing beat dollar cost averaging about two-thirds of the time. That’s because markets historically increase about two-thirds of the time (or two out of every three days). Staying invested for a longer period of time improves the likelihood of capturing positive market returns.

PWL Capital’s Benjamin Felix also looked at this problem in a 2020 study and confirmed that lump sum investing outperformed dollar cost averaging about two-thirds of the time. This analysis took a broader look at different stock market outcomes throughout history, including when stock prices were high, and during bear markets. Even in these extreme situations, dollar cost averaging underperformed lump sum investing 53.66% of the time during bear markets and 63.70% of the time when stocks were trading in the 95th percentile of historical valuations.

The evidence supports investing a lump sum of money all at once (and immediately). Investors will gain exposure to markets as soon as possible. Stock returns exceed the returns of cash (the equity risk premium) and putting your lump sum to work in the market right away takes advantage of this growth opportunity.

The Behavioural Answer

Psychologically, it’s much more difficult to invest a large sum of money all at once. The concept of loss aversion tells us we’d much rather avoid losses than acquire an equivalent gain. The pain of losing is about twice as powerful as the pleasure of winning. There’s also fear and regret that the decision may turn out to be wrong in hindsight, making us more averse to taking on risk.

While dollar cost averaging has proven to be a less optimal way to invest a sum of money, it may be more palatable from a behavioural perspective. Still, we want to take an evidence-based approach to dollar-cost averaging.

Knowing that we cannot successfully predict the direction of the stock market, it does not make sense to try to time the market in order to avoid post-investing regret.

If you decide to dollar cost average — or invest gradually over a period of time – it’s best to take a systematic approach. That means setting a pre-determined investing schedule rather than relying on your emotions or intuition around when markets ‘feel’ safe.

Let’s say you have a lump sum of $200,000 to invest. A systematic and pre-determined schedule could mean investing $20,000 on the first of every month for 10 months until the full amount is invested.

Again, the math favours lump sum investing, so if you choose the dollar cost average approach, you’re accepting that you’ll likely have lower expected long-term returns (because stocks outperform cash), and that delaying your investment is itself a form of market timing, which is something few investors can successfully pull off.

Once interesting conclusion from Mr. Felix’s paper suggested that if an investor cannot bear to invest a lump sum all at once, perhaps a more risk-appropriate portfolio should be adopted.

“Given the data supporting lump sum investing we believe that there is a strong statistical argument to avoid dollar cost averaging unless it is absolutely necessary from a psychological perspective, and if that is the case, we believe that the long-term asset allocation may need to be revised toward a more conservative portfolio.”

In this case, the lump sum approach would still make the most sense, but instead of allocating 80% or 100% of the portfolio to stocks, perhaps a more conservative allocation of 40% or 60% stocks would make investing the lump sum feel less risky.

The Verdict

You should invest a lump sum of money immediately rather than dollar cost averaging over time. But if the fear of loss and regret is too strong to bring yourself to invest the entire amount at once, design a systematic approach to invest smaller portions at regular intervals or, more preferably, adjust your asset allocation towards a more conservative portfolio before taking the plunge.

Investing When Markets Are At An All-Time High

Investors get nervous when stocks reach new all-time highs. Record high stock prices are often seen as a precursor to a market correction or crash. That intuitively makes sense. After all, no bull market lasts forever.

Indeed, the average length of a bull market (measured by a stock market rise of at least 20% from its previous low) has been 1,742 days – or about four years and nine months. The average length of a bear market (measured by a stock market that has fallen at least 20% from its previous high) has been 363 days – or about one year.

The key takeaway is that stock prices reach all-time highs more frequently than you think. In 2020 alone, U.S. stocks reached 30 new all-time highs. Since the great financial crisis in 2008-09, the S&P 500 has seen more than 270 all-time highs. That’s about 14% of all trading days where stock prices closed at an all-time high.

Going back 100 years, U.S. stocks reached all-time highs on about 5% of all trading days. Those new highs tend to cluster during bull markets, but there can be long droughts when stock prices won’t reach new highs for many years.

| Peak | Trough | Drawdown | New Highs | # of Years |

| Sept 7, 1929 | June 1, 1932 | -86.2% | Sept 22, 1954 | 25.1 |

| Jan 11, 1973 | Oct 3, 1974 | -48.2% | July 17, 1980 | 7.5 |

| Mar 24, 2000 | Oct 9, 2002 | -49.1% | May 30, 2007 | 7.2 |

| Oct 9, 2007 | Mar 9, 2009 | -56.8% | Mar 28, 2013 | 5.5 |

Investors would obviously prefer to avoid investing a lump sum at the wrong time, as it would take several years to recover their losses.

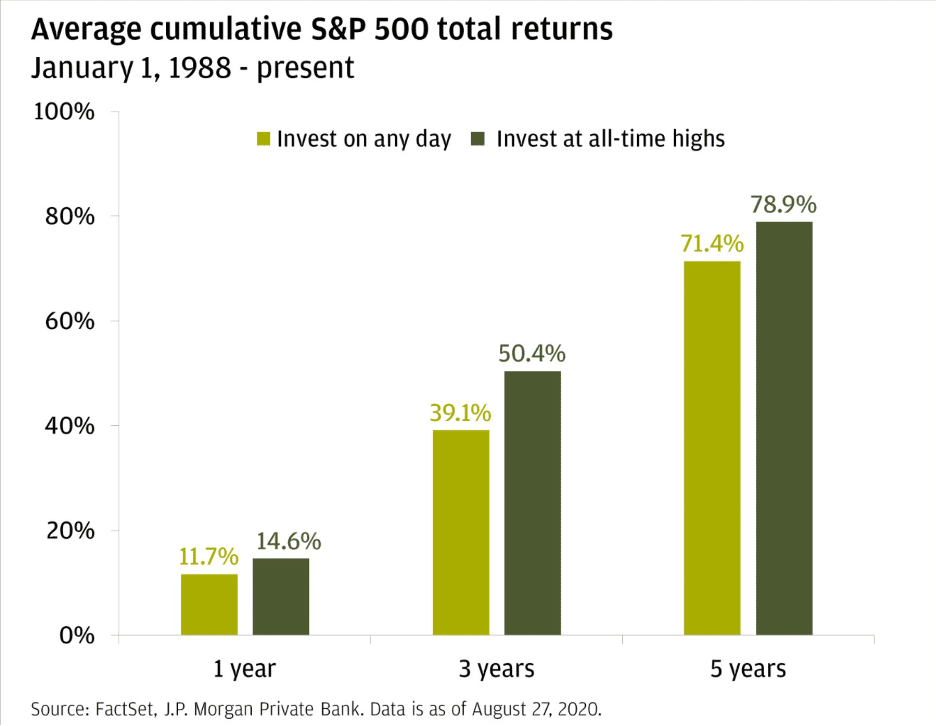

But the evidence shows why investing at all-time highs isn’t as frightening as it seems. Research from JP Morgan found that if you invested in the S&P 500 on any random day since the start of 1988 and reinvested all dividends, your investment made money over the course of the next year 83% of the time. On average, your one-year total return was 11.7%.

That’s comforting, but not surprising. The most surprising takeaway was when the study looked at investing only on days when the S&P 500 closed at an all-time high. The results we’re actually better! Your investment made money over the course of the next year 88% of the time, and your average total return was 14.6%.

Investors will always have reasons to feel anxious about the future. The outcome of current and future events is unknown, which clouds our judgement and ability to assess risk. Investors tend to be even more anxious when stock prices reach an all-time high or have reached all-time highs more frequently than their historical average. That’s because it feels like any calamity may cause the next great stock market crash.

But the evidence shows us that stocks reach all-time highs more often than we realize. Stock prices increase over time and rise more frequently than they fall. Bull markets also last longer than bear markets, and prices rise much higher in bull markets than they fall in bear markets.

The best approach is to invest for the long-term in a risk-appropriate portfolio. Stay invested and contribute regularly, regardless of market conditions (such as new highs or lows).

The Verdict

Investing when stocks are at an all-time high led to better outcomes than investing on a random day. It reinforces the notion that time in the market is better than timing the market. Investors with a long-time horizon should confidently ignore current market conditions and stick to their investment plan.

Time Diversification (or Should Young Investors Use Leverage?)

Stocks have a higher expected return than other less risky asset classes like bonds and cash. This risk premium leads some investors to consider borrowing money to invest.

Leverage can amplify returns, but the risk cuts both ways. If the investment goes down in value, then the investor is still on the hook for the borrowed amount (with a less valuable asset to secure the loan).

The idea of using leverage to generate higher returns is nothing new. Most homeowners used leverage to buy their home, contributing 5% to 20% from their own savings and financing the remainder with a mortgage. It’s not uncommon for homebuyers to use 10:1 leverage to purchase their home (e.g. a $45,000 down payment and a $450,000 mortgage).

Young borrowers cannot afford to pay for a home in cash, so they obtain a mortgage and pay it off over 25 years. Indeed, a mortgage is simply a fact of life for the vast majority of Canadian homebuyers.

While borrowing to purchase a house is widely accepted, borrowing to invest in stocks is less palatable. But the same concept can apply to investing. When we’re young, we have a long time-horizon but less money to invest. When we’re older, we have more money, but less time for compounding to work its magic.

What if young investors used leverage to gain more exposure to stocks and take advantage of their long time-horizon?

That’s exactly what Yale professors Ian Ayres and Barry Nalebuff proposed in their 2010 paper called, Diversification Across Time. The authors looked at stock data going back to 1871 to show that early leverage helps investors maximize retirement savings and minimize risk.

While investors have learned the importance of diversifying their investments across asset classes and geography, they haven’t recognized the value of diversifying across different time periods.

“The problem for most investors is that they have too much invested late in their lives and not enough early on,” said the authors.

Indeed, most people start with little to no savings when they are young. The authors assumed a 44-year investing cycle (from 21 to 65) where investors use 2:1 leverage in their early years before slowly deleveraging over time. The authors suggest that young investors should also allocate 100% of their portfolio to stocks until their target level of equity investment is achieved.

The results showed that if people had followed this advice, historically they would have retired with portfolios worth 21% more on average when compared with investing 100% in stocks with no leverage.

There’s a cost to borrowing and the authors used a margin cost of 5% compared to equity returns of 9%. This equity premium served as the source of additional returns in the study’s model. Even if that premium was 2%, the authors found that investors would still benefit from using leverage in their early years.

The authors also conceded that despite the study’s compelling results, many people have a strong aversion to using leverage to invest in stocks. That, coupled with poor investor behaviour (market timing, chasing past performance, little understanding of the importance of costs and diversification) make it impractical for most people to apply a long-term leveraging strategy to their portfolios.

“Leveraged strategies expose workers to a much larger probability of incurring a substantial negative monthly return sometime during their working lives,” said the authors.

The Verdict

Young investors in their 20s and 30s might consider using 2:1 leverage (e.g. invest $20,000 total by using $10,000 of your own money and $10,000 from a loan) to increase their stock exposure until a target level of investment is achieved. This approach uses time diversification to enhance retirement savings outcomes with less risk.

Young investors employing this strategy should also increase their stock allocation to 100% to take advantage of the equity premium.

This strategy comes with a major caveat: leveraged investing can lead to substantial losses. Deploy it with eyes wide-open to the possible risks.

Home Country Bias vs. Global Diversification

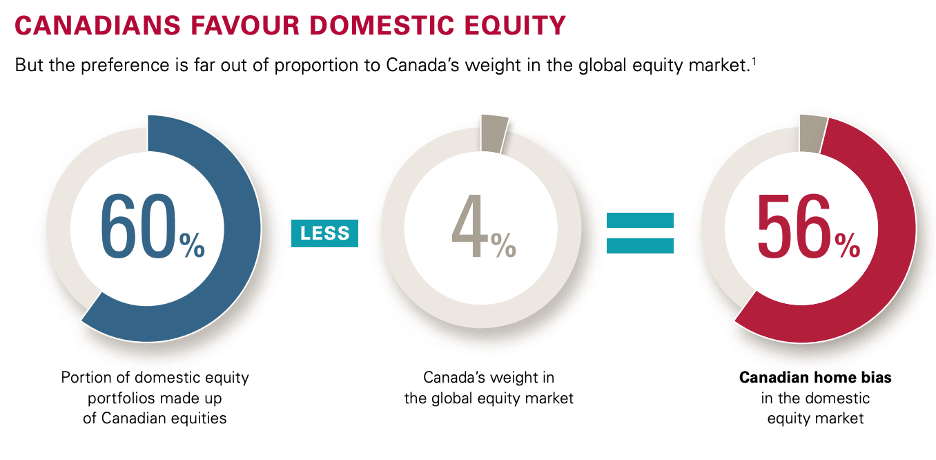

Canadian investors have a serious home country bias when it comes to their investments. On average, the equity component of a Canadian investor’s portfolio contains 60% Canadian stocks.

Home bias is not uncommon. Investors in most countries prefer their domestic stocks over foreign stocks. Chalk it up to buying what you know. In large, diverse markets like the United States, home bias is not a big deal. But in a country like Canada, which makes up just 4% of global equity markets, a strong home bias can lead to a significantly less diversified portfolio.

Canada’s market is heavily concentrated in three sectors: financials, energy, and materials. Sectors like healthcare are almost non-existent. 37% of Canada’s equity market is represented by the 10 largest companies (compared to just 7% of the world’s equity market represented by the 10 largest companies).

Because of this security and sector concentration, an all-Canada stock portfolio has historically been more volatile than portfolios with international stock diversification.

However, investing in Canada does come with some benefits. Canadian stocks benefit from the dividend tax credit, while foreign stock dividends do not receive any favourable tax treatment. That alone leads to 0.30% more return in a taxable portfolio.

Canadian stocks are also not subject to foreign withholding taxes. While foreign withholding taxes are recoverable in some case, the cost in a TFSA can be as high as 0.50%.

Finally, we live in Canada and spend Canadian dollars. Investing in foreign equities exposes investors to foreign currency risk, as those investments must be converted back to Canadian dollars to be spent in future years.

Global diversification is important, but we don’t need to precisely follow market cap weights to get the full benefits of global diversification.

Vanguard found that the maximum expected volatility reduction was achieved when a Canadian investor allocated 50-60% of their equity portfolio to foreign stocks. Allocating any more than that actually increased volatility.

Fees and taxes also make the cost of investing in foreign stocks more expensive than investing in Canadian stocks. And, behaviourally, we might feel bad having too little exposure to Canadian stocks when the Canadian market is performing well. After all, we pay closer attention to what’s happening within our borders and less so with, say, Swedish or German stocks.

The ideal allocation to Canadian equities is clearly not 60%, but it’s also not 4%. To determine the right home country bias for your portfolio, you can look to the construction of asset allocation ETFs designed by Vanguard and iShares.

Vanguard assigns a 30% weight to Canadian equities through the Vanguard FTSE Canada All Cap Index ETF. It allocates 41.30% to U.S. stocks, 20.8% to stocks in developed countries outside of North America, and 7.9% to stocks in emerging markets.

iShares assigns a 23.2% weighting to Canadian equities through the iShares S&P/TSX Capped Composite ETF. It allocates 47.6% to U.S. stocks, 23.6% to stocks in developed markets outside of North America, and 5.1% to stocks in emerging markets.

It’s safe to conclude that allocating 20-30% of your equity portfolio to Canadian stocks is ideal for lowering overall portfolio volatility, lowering fees and taxes, and feeling good about your portfolio when Canadian stocks are performing well.

The Verdict

Canadian investors have a strong home country bias with 60% of the equities in their portfolio allocated to domestic stocks. Canada makes up just 4% of global markets. Diversifying your investments across the globe is important, but some home country bias is reasonable because it actually reduces volatility, fees, and taxes.

While there’s no ideal home bias for Canadian investors, a sweet spot might be in the 20-30% range.

Final Thoughts

Investing has been democratized for millions of investors around the world. We no longer need expensive advisors or flashy market timing gimmicks to access the global markets. Today, we have online brokers and robo advisors where investors can build a low cost, globally diversified, and risk appropriate portfolio of investments that can trounce the returns of traditional active investing strategies.

At the same time, the behavioural challenges that come with investing haven’t got any easier. Investors still struggle to control their emotions. They struggle with loss aversion and FOMO. They struggle with analysis paralysis because of all the tools and investments options at their fingertips.

That’s why we look to the evidence to help guide us through the decisions that every investor is going to face throughout their investing journey.

Decisions like whether to capture the market returns through low-cost index funds and ETFs, or to try to beat the market with a more active approach. Decisions like what to do with a lump sum of money, and whether to invest it all at once or dollar cost average over time. How much home country bias is appropriate? Should I use leverage? Where the heck should I put my bonds? And, does gold actually provide a hedge against inflation?

There is a significant amount of academic and empirical evidence that can help us make these decisions. The key is to sort through the bafflegab (marketing speak from the investment industry) and look for the evidence.

I hope you found that here with this evidence-based guide to investing.

References and Links

Passive Investing versus Active Investing

Harry Markowitz, “Portfolio Selection”, the American Finance Association, (1952)

Eugene F. Fama, “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work,” Journal of Finance 25, no. 2 (May 1970)

SPIVA statistics and reports

William F. Sharpe, “The Arithmetic of Active Management”, The Financial Analysts' Journal Vol. 47, No. 1, January/February 1991. pp. 7-9, 1991

Lump Sum Investing versus Dollar Cost Averaging

Vanguard Group, “How To Invest A Lump Sum Of Money”, 2012

Benjamin Felix, Portfolio Manager, PWL Capital Inc., “Dollar Cost Averaging vs. Lump Sum Investing”, 2020

Investing when markets are at an all-time high

Bloomberg L.P. Returns from 10/22/1957 – 12/31/2019

Time Diversification

Ayres, Ian and Nalebuff, Barry, Diversification Across Time (October 4, 2010). Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 413

Home Country Bias versus Global Diversification

Vanguard Group, Global equities: Balancing home bias – A Canadian investors’ perspective by David Pakula, David Walker,David Kwon, Paul Bosse, Vytautas Maciulis and Christopher B. Philips

Hi Rob,

Good overview of evidence-based investing.

I think a few things need to be added to your article.

– More emphasis on things you can control, especially fees. A separate section on the impact of fees on returns would be good.

– More nuance on market efficiencies. Markets are more or less efficient over the long haul, especially developed markets, and more especially the S&P 500. However, emerging markets are less efficient.

– A section on investing in bad markets. This would include data on returns when investing at all-time lows. Just add another bar to the graph Average Cumulative S&P 500 Total Returns.

Appreciate the feedback, Gail – thank you!

Excellent article Robb. Will share with the adult children: one likes to stock pick risky stuff and the other has not started to invest at all.

Hi Kathryn, thanks for the kind words – appreciate you sharing my work!

Hi Robb,

Thank you for a great article that I can share with my young adult son to set him up to be successful financially. I have started buying VEQT in my personal and corporate accounts. Question – When I hit retirement in about 8 years should I stay the course with VEQT or buy some good dividend stocks for the cash flow? Thank you, Alice

Hi Alice, thank you!

Alice, I can’t say whether holding an all equity portfolio would be suitable for you in retirement without knowing a lot more about your situation and other available resources. What I can say is there’s no need to switch to a dividend focused strategy in retirement. You can create an income stream from an ETF portfolio taking the distributions (typically around 2% of the portfolio) and topping that up by selling units or shares of the ETF to generate your required income. This is what’s called a total return approach to generating retirement income.

In general, using evidence-based investing is a good thing, but it’s possible to take it too far. The problem stems from the limited amount of data available, which leads to data mining. One example of this is the people who show graphs of how the Shiller CAPE has accurately predicted 10-year returns during the past three decades or so. This is just a statistical fluke based on very limited data.

A more subtle case of limited data is in Ben’s paper on DCA vs. lump-sum investing (LSI). He looks at what happens when the Shiller CAPE is in it’s 95th percentile (for US stocks). The mathematical treatment masks the fact that this focuses on very little data. I have no doubt that LSI beats DCA on average. However, we don’t have enough data to reject the hypothesis that DCA offers sufficiently lower volatility that it is a reasonable choice. I’ve always done LSI myself, but if I got a lump sum exceeding my previous net worth, I’d definitely look into whether DCA offers more than just behavioural comfort.

Hi Michael, agree that we can take things too far with data. Just look at the backtesting and data mining done to create new and wonderful investing strategies. CAPE is another great example that I know you’ve been critical of lately.

The LSI vs DCA debate is an interesting one. One subtlety in these examples is that just because DCA happened to be “less optimal” than LSI doesn’t necessarily mean it led to a bad outcome. I also think Ben’s point about using a more conservative portfolio is really important. The type of investors I’ve come across who are agonizing over investing a lump sum tend to be fairly conservative investors to begin with. They tend to frame their decision as if they are investing the entire amount in equities, which is not usually the case.

LSI vs. DCA is a lot like the fixed vs. variable mortgage debate. There’s good evidence showing that variable rates saved homeowners money the vast majority of times. But that doesn’t mean choosing the fixed rate is a bad option – just likely to be less optimal. Then again there are behavioural aspects (sleep at night factor) that favour fixed rates.

Wow, great post! A wonderful summary of key aspects of evidence based investing. One minor edit… I think you’re math is a bit off here, just to show I’m paying attention!

“Let’s say you have a lump sum of $240,000 to invest. A systematic and pre-determined schedule could mean investing $20,000 on the first of every month for 10 months until the full amount is invested.”

Hi Greg, no the math was right. I just assumed you took the remaining $40k and booked a trip to one of those overwater bungalows in Maldives 😉

Good catch, typo fixed!

Thanks Robb for another great article. I’m a believer in evidence based investing and I think the best investment strategy is one that an individual can stick with over the long term. The asset allocation consideration in the DCA versus LSI section was very interesting. If a given asset allocation is already appropriate for someone, then the mathematically correct DCA should be the clear choice; it makes sense for the two things to be in sync.

In my view, there are only a few reasons to change one’s asset allocation. E.g. If it’s not the risk appropriate one, if life circumstances have changed, etc. None of which have to do with market conditions.

If a windfall-like amount was the result of a life event or could change one’s circumstances, and the DCA vs LSI question looms large, I think that would be a good indication that the asset allocation should also be revisited. Things such as a large inheritance, winning the lottery, a corporate buyout or vesting scenario, an insurance payout. Not all of these are necessarily associated with something “good” happening either.