I’m Single. Can I Afford To Buy A Home?

Canada is in a full blown housing crisis. While much of the housing conversation centres around sky high prices in Toronto and Vancouver, affordability issues stretch across the entire country. The average home price in Canada was $650,140 as of August 2023. This is especially problematic for single Canadians.

Canada’s single population has increased steadily since 2000. According to Statista, there were more than 18 million singles living in Canada in 2022 (9.67M men and 8.60M women).

What’s a single with homeownership aspirations to do? It’s a difficult question without a lot of satisfying answers.

- Earn higher than average income consistently throughout your career

- Curb expectations for how much house you can realistically afford

- Be willing to sell the home to help fund retirement spending

- Find a partner with whom to share expenses

Easier said than done.

Let’s take a closer look at a real life situation. Katherine is 33-year-old single living in Calgary, Alta. She earns $80,000 per year working for a mid-sized company, with no pension and no employer matching savings plan. She plans to retire at age 65.

Katherine loves her apartment – it’s close to work and to all of her favourite amenities. Best of all, she pays just $1,600 per month in rent as a long-time tenant. Her total after-tax spending is $54,000 per year.

Despite her current situation, Katherine does feel pressure (FOMO) to buy a home and wants to know if home ownership is possible without derailing her finances. She opened a First Home Savings Account (FHSA) this year and plans to fund it with $8,000 before year-end. She’ll continue to prioritize the FHSA for the next four years, and aims to buy a home in 2028.

Price point matters, and Katherine is looking at condos in her area that are currently listed for $400,000. She thinks it would be realistic to budget $450,000 for such a condo in 2028. She’d prefer to put 20% down ($90k) to avoid CMHC premiums.

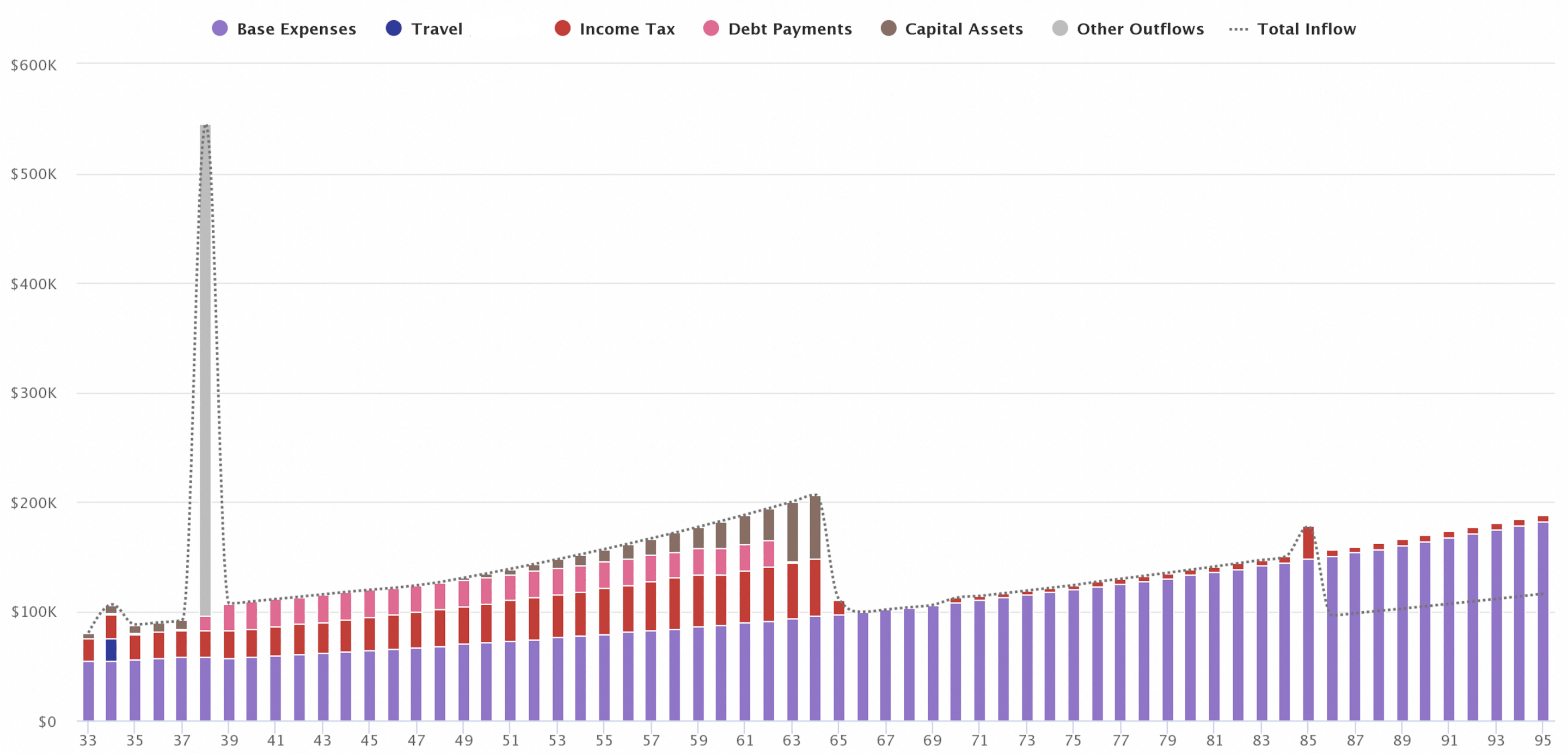

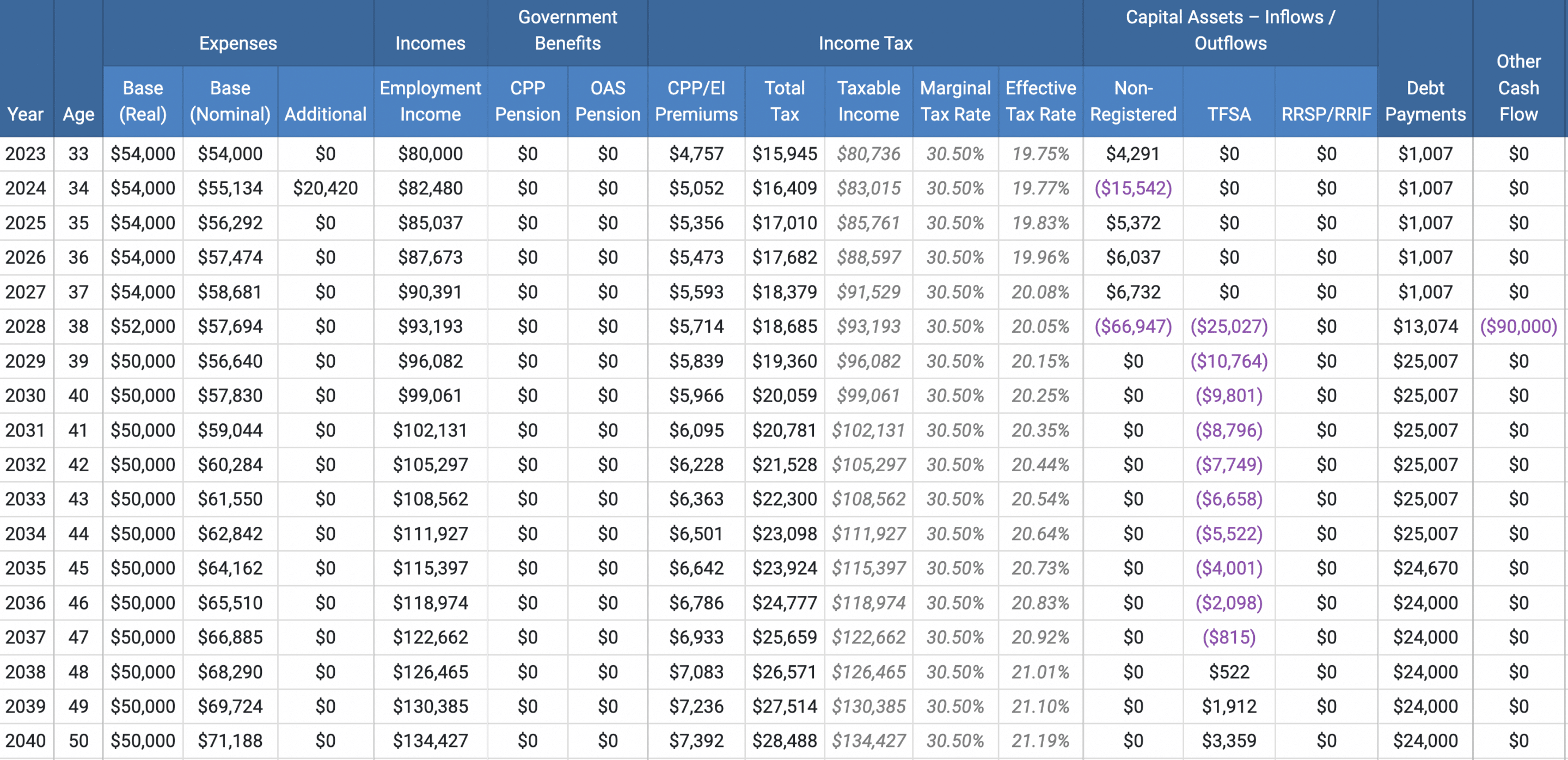

The numbers start to paint a picture as we model this out over Katherine’s lifetime.

First, we need to know how Katherine’s expenses will change when she becomes a home owner. We’d eliminate the rent expense of $1,600 per month ($19,200 per year), but then we must add phantom home ownership costs like house insurance ($2k), property taxes ($4.5k) and maintenance ($4.5k). So, Katherine’s after-tax spending goes from $54,000 down to $45,800.

But, she also expects to buy a new car around that time, so we should budget an additional $350 per month ($4,200 per year). That brings the after-tax spending back up to $50,000.

We also need to factor in the mortgage, which will come to $2,000 per month ($24,000 per year). At an average borrowing rate of 4.4% over the life of the mortgage, the home will be fully paid off by 2053 (25 years). That aligns with Katherine’s desire to enter retirement mortgage-free.

Let’s stop and think about the implications of buying a home. A straight “rent versus mortgage” comparison shows that Katherine would only need to increase her budget by $400 per month and she can happily own her own home instead of flushing rent money down the toilet.

A savvier evaluation shows that the total cost of home ownership is closer to $2,916 per month (mortgage + property taxes, insurance, maintenance) – an increase of more than $1,300 per month. Katherine is now spending $74,000 per year to live the same lifestyle as a home owner.

The implications here are massive. Remember, Katherine does not have a workplace pension or savings plan. She’s on her own to contribute to her retirement accounts, and the focus for the next five years will be on funding the FHSA so she can buy a home in 2028. She’s no longer contributing to her RRSP or TFSA.

Fast forward to 2029 (post home purchase) and Katherine is adjusting to her new reality of spending $74,000 per year. The painful reality is that Katherine will be in a cash flow deficit for nine years, where she’ll have to withdraw from existing savings to meet all of her spending needs. This assumes both spending and income increase by 2.1% annually.

Katherine will need to ramp-up her savings big-time from age 50 to 64. Indeed, it’s possible for her to save and invest her way to about $780,000 across her RRSP and TFSA accounts by the time she turns 65. The house is also paid off, and is now worth nearly $800,000.

Is it possible for Katherine to retire and maintain her standard of living while remaining in her house? Unlikely.

In this scenario, Katherine runs out of money at age 85 and would need to unlock her home equity through an outright sale, a downsize (but she is already in a condo), or a reverse mortgage to maintain her standard of living.

That, or reduce her spending to $45,000 per year (a 10% reduction in today’s dollars) from age 65 onward. Not ideal, but certainly possible.

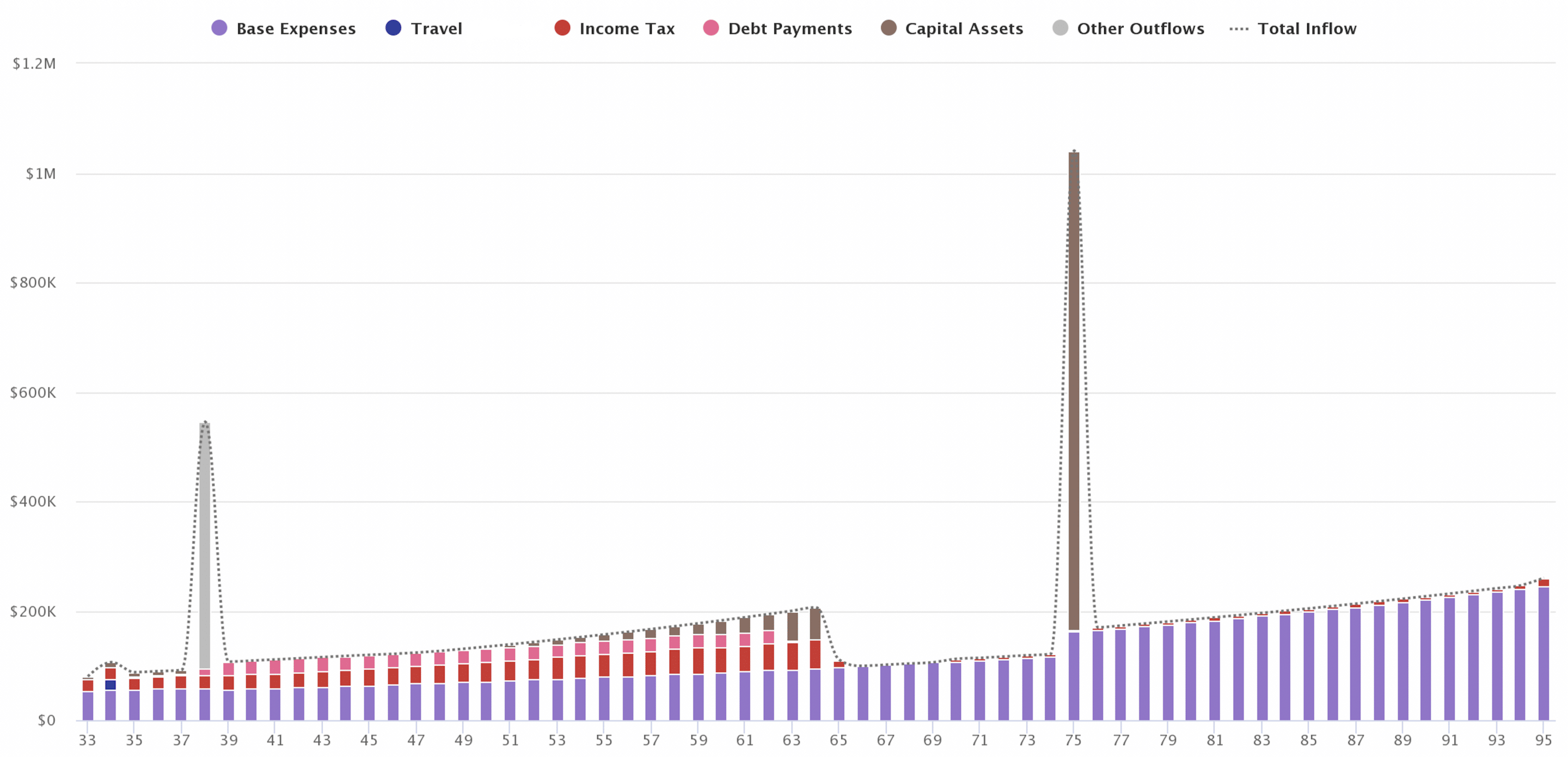

It might be wise to sell the house at age 75 and rent for the remainder of her life. Doing so allows Katherine to spend $67,415 per year in today’s dollars, which would be enough to pay for rent and still maintain the same (or better) quality of life to age 95.

Final Thoughts

This is just one example of a single woman buying a modest home in a major Canadian city by age 38. Katherine has above average income and lives in a city where condos can still be purchased for less than $500,000.

Still, things are tight. Katherine won’t have the cash flow to contribute to her retirement savings for more than a decade while she saves up a downpayment and then adjusts to the new and expensive reality of carrying a mortgage and other phantom costs.

She starts saving again (modestly) by age 48, but won’t even get her savings rate up to 10% of gross income until age 58. That’s a lot of heavy lifting to do in her final working years to build up an appropriate amount of retirement savings.

And, this assumes everything goes according to plan. Income continues to increase with inflation, and spending remains constant (in today’s dollars) throughout her working career. In reality, she may have multiple vehicle purchases, planned home renovations, unplanned home and auto repairs, income interruption of some kind, a bucket list vacation expense, etc.

Of course, the opposite is also true. It’s more likely that income increases by at least inflation + 1% each year (on average between merit, cost of living, and promotions over time). It’s also possible that Katherine finds a partner with whom to share expenses. This would significantly change Katherine’s cash flow throughout her working career and into retirement.

For singles in higher cost of living areas, home ownership is likely out of reach for all but the top 10-20% of income earners.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. Renting has a certain stigma, at least here in Canada, but more and more of my clients across Canada are realizing that “drive until you qualify” doesn’t lead to a higher quality of life. Indeed, a longer commute in a suburb far away from the vibrance and liveliness of the city may not bring you long-term joy (home ownership be damned).

One client quickly realized this and chose to sell the suburban home he bought just a year ago and move back to renting an apartment in the exact neighbourhood he wanted nearby his work and social life.

In any case, the home ownership dream for single Canadians is on life support and will require more careful analysis (case-by-case) in higher cost of living centres. Consider the trade-offs and whether they’re worth it to pursue your dream of buying a home as a single.

I enjoyed this perspective. My own experience, back in the mid 90’s when I graduated and started out in the workforce was that I never would have considered home ownership as a single person. I started out renting on my own, then when I found my “to be” wife, we rented a condo for 18 months. We had each accumulated a fair bit of savings and lived frugally while we saved for our eventual home purchase.

When I was single, it was inconceivable to me to consider home ownership (of any kind). 30 years later home affordability is much tougher and I do worry that my children will be forced to double or triple the length of time that they need to save. I also worry that they don’t have the fortitude to live the kind of frugal life my wife and I lead while we set aside virtually every penny to reach our goals. I certainly believe they’ll have to wait until they “partner up” to achieve such a goal.

I admire any individual, or any couple who can take the steps to reach their home ownership objective in today’s economic environment, but I agree, as your model shows, it’s not necessarily the best fiscal decision (but of course, having a home is not solely a fiscal decision).

The old adage of I don’t want to may my landlord’s mortgage is slowly getting flipped to “hell yeah, I’ll let some other guy pay the exorbitant interest while I rent and save” – or is it? Time will tell.