The federal government uses the inflation data for the 12-month period between October 1 to September 30 to determine a number of figures for the following calendar year. September’s inflation rate was announced earlier this month, so we now have the entire data set needed to calculate the indexing rate for 2024, which gives us a new TFSA limit, OAS clawback threshold, tax brackets, and more.

Thanks to Aaron Hector for doing the math to give us these important details.

The indexing rate for 2024 will be 4.7%. That’s down from 6.3% in 2023. If you are receiving a federal pension, expect your benefits to increase by 4.7% as of January 2024.

Note that the indexing rate for CPP is based on a different calculation (inflation data for the 12-moth period between November 1 to October 31), so the rate may be different. Last year’s CPP increase was 6.5% based on 2022 inflation data.

The TFSA contribution limit will increase to $7,000 (up from $6,500 in 2023). This marks the second consecutive increase in the annual limit. The TFSA lifetime limit for those eligible since 2009 will be $95,000.

The OAS clawback threshold will increase to $90,997 (up from $86,912 in 2023). That means those collecting OAS can earn up to $90,997 in taxable income in 2024 without fear of having to repay their benefits.

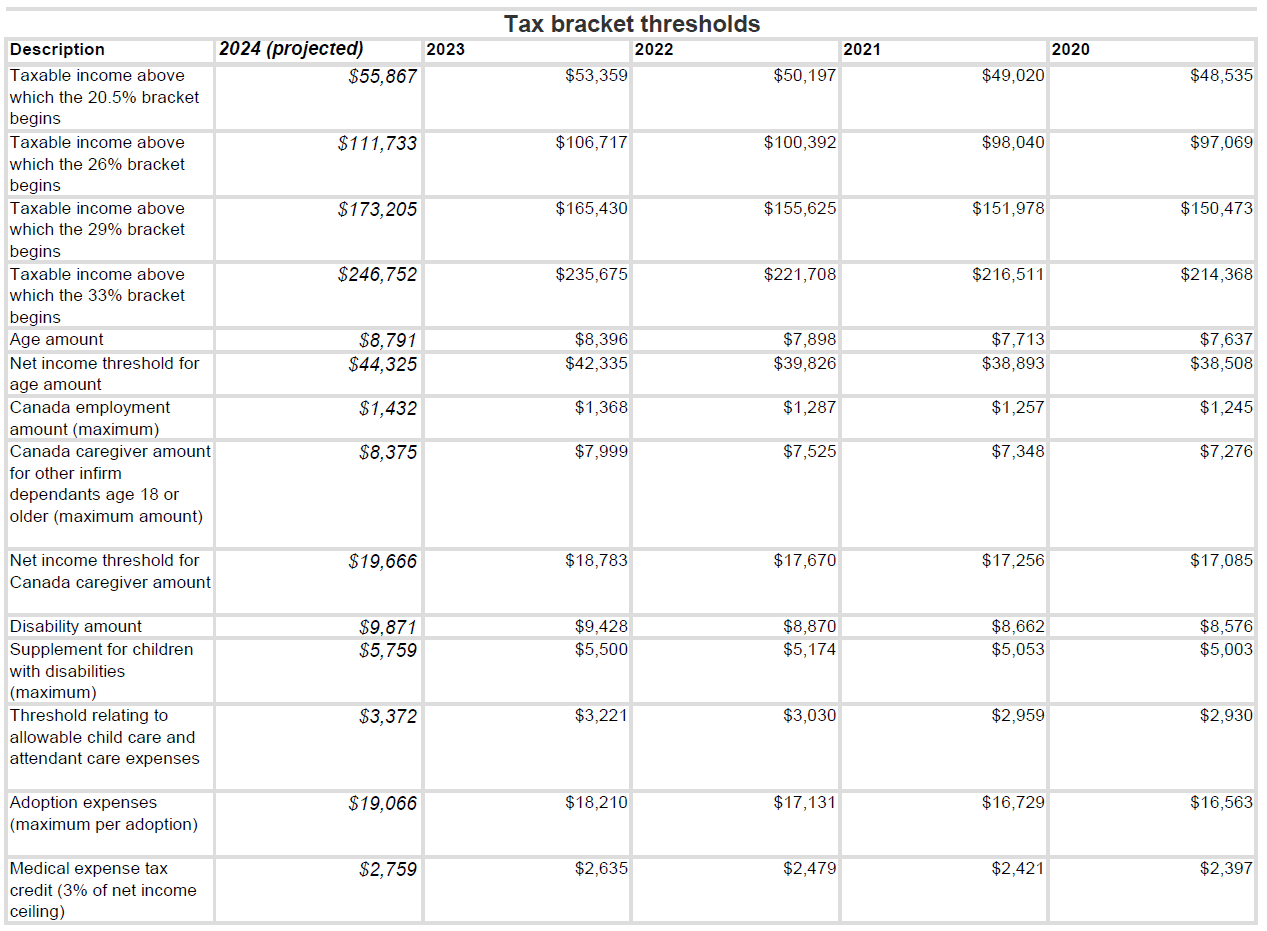

A host of tax bracket thresholds will be updated for 2024:

The year’s maximum pensionable earnings (YMPE), which is the maximum salary amount on which you need to contribute to the Canada Pension Plan, is increasing to $68,500 (up from $66,600).

Budgeting nerds like me can use these figure to update their spreadsheets and forecasts for 2024.

If you were planning to max out your TFSA next year, make sure to budget $7,000 instead of $6,500.

Of note for me and my wife, we aim to keep our taxable income at the top of 30.5% marginal tax bracket so we can safely increase our income (the amount we pay ourselves from our small business) by 4-5% next year.

The one small silver lining of higher inflation over the past two years is that our tax brackets and a bunch of other important figures are also indexed to inflation.

This Week’s Recap:

Earlier this month I updated my article on how to crush your RRSP contributions next year. It’s a reminder for those who contribute significantly to their RRSPs to use the T1213 form to request to reduce tax deductions at the source.

Despite the current interest rate environment I still come across many people who are interested in real estate investing as a source of passive income. Reality check: There’s nothing passive about owning a rental property, and with rates where they are right now the odds of your property being cash flow positive are vanishingly small.

Remember, you can’t go back in time and replicate the returns that your parents, friends, co-workers experienced over the past decade or more. Your starting point is now, in this current environment of sky-high real estate prices and higher interest rates. Adjust your expectations accordingly.

Who in their right mind is thinking right now, you know what – a couple of income properties might just be the ticket to financial freedom?

— Boomer and Echo (@BoomerandEcho) October 23, 2023

Promo of the Week:

A reminder if you want to up your credit card rewards game for better travel experiences then you should really be using American Express cards to maximize your points.

Even better if you can use American Express’s referral program to “activate your player 2” (e.g. your partner) to earn points faster. That’s what my wife and I have been doing over the past few years.

We use Aeroplan for our flights and Marriott Bonvoy for our hotel rewards. The best way to accumulate Aeroplan miles and Bonvoy points is to collect American Express Membership rewards points and then transfer the points to those respective programs.

Here’s our credit card line-up to get you started:

- The American Express Platinum card – Earn up to 100,000 Membership Rewards points.

- The American Express Aeroplan Reserve card – Earn up to Aeroplan points.

- The American Express Cobalt card – Earn up to 30,000 Membership Rewards points and 5x points on food and drink (this is my main every day credit card).

- The Marriott Bonvoy American Express card – Earn up to 55,000 Marriott Bonvoy points and a free night certificate.

And, for small business owners, even more lucrative rewards await:

- The Business Platinum Card from American Express – Earn up to 120,000 Membership Rewards points.

- The Marriott Bonvoy Business American Express card – Earn up 55,000 Marriott Bonvoy points and a free night certificate.

Happy travels!

Weekend Reading:

Overwhelmed by all the negative news? Here’s why you might need financial therapy.

Certified Financial Planner Shaun Maslyk explores what financial freedom means in Canada.

Anita Bruinsma writes about personal finance hogwash – five phrases you need to stop feeling bad about:

“The truth is that most people should be using traditional methods for achieving financial stability. Yes, it’s boring, yes, it takes time and yes, it takes sacrifice and self-discipline, but wealth and financial stability don’t come free and easy.”

If you knew when you were going to die and the money you would leave, what would you do differently?

Rising rates, inflation, and housing affordability aren’t the only reason early retirement plans don’t pan out.

Michael James on Money shares what experts get wrong about the 4% rule.

What you can expect from the Canada Pension Plan and why it won’t run dry anytime soon.

Advice-only planner Jason Evans explains the danger of using the CPP breakeven calculation.

Speaking of CPP, here’s a really informative Q&A on Alberta’s attempt to form its own pension plan (APP):

(🧵). In light of the major debate happening in Alberta, I thought I would try to put together a FAQ on a CPP/APP. As always, the answers here do not contain legal advice or personal views.#ableg #CPP

— Timothy Huyer (@tim4hire) October 27, 2023

Beating the stock market isn’t easy. So why do many Canadian investors act like it is? (subs).

Finally, in his latest Charting Retirement post Fred Vettese asks if dementia risk is part of your retirement plan. Some sobering statistics for those over 85 years old.

Have a great weekend, everyone!

A few months ago I wrote about some changes I plan to make to our kids’ RESP portfolio. We’ve used TD’s e-Series funds for this account, but will switch to an ETF portfolio using Justin Bender’s excellent RESP strategy.

Along with this portfolio reboot, I’ll also change how we fund the account (annually versus monthly). But I’m afraid I’ve lost track of their total contributions and grants after many years of benign neglect automatic monthly contributions.

I called the Canada Education Savings Program hotline at 1-888-276-3624 and requested a Statement of Account for each child (note, you have to ask for this to be mailed otherwise the agent will just read the numbers to you over the phone).

Once I had the total contributions and grants per child, I calculated each child’s share of the investment returns:

| Child | Contributions | Grant | Investment Growth | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanguard (14) | $26,000 | $5,200 | $16,905 | $48,105 |

| iShares (11) | $24,000 | $4,800 | $15,605 | $44,405 |

| Total | $50,000 | $10,000 | $32,510 | $92,510 |

I knew right away there was a problem. Our goal is to contribute $36,000 per child to attract the maximum CESG of $7,200 per child. But if we continue regular monthly contributions of $208.33 per child then our oldest is going to be short. By the end of the year in which she turns 17 we’ll have only contributed $34,125.

This makes sense because while we opened the RESP right after our oldest child was born, we did not contribute the maximum annual amount. We started with what we could afford, which was $50 per month. That gradually increased to $208.33 per month – but that took a few years.

We’re going to have to catch up on a missing grant by contributing $5,000 in January, 2024. That, plus a regular $2,500 contribution in 2025 and a contribution of $1,875 in 2026 will fully max out the CESG for our oldest child.

Meanwhile, we’re right on track to contribute $36,000 by the time our youngest child is 16. We’ll do annual contributions of $2,500 from 2024 to 2027, and then contribute $1,400 in 2028 (her age 16 year) to fully max out the CESG for our youngest child.

The lesson here for those of you who did not max out your RESP contributions in the first few years is to get that Statement of Account for each child so you know exactly where you stand today, and so you can make a plan to catch up on the unused grants before it’s too late.

According to the Government of Canada website, beneficiaries qualify for a grant on the contributions made on their behalf up to the end of the calendar year in which they turn 17 years of age.

This Week’s Recap:

Earlier this month I wrote about when life insurance is sold, not bought. Still fuming about that one…

A reminder that the Canadian Financial Summit is back for its seventh year with a great line-up of speakers.

This year’s conference takes place from October 18th to 21st. You can grab your free ticket here.

Promo of the Week:

Maybe you’re ready to plan your revenge travel year in 2024, or you’re just looking to switch up a stale credit card rewards program and get into something more lucrative.

My pro tip is to use Aeroplan for your flights and Marriott Bonvoy for your hotel rewards. The best way to accumulate Aeroplan miles and Bonvoy points is to collect American Express Membership rewards points.

Here’s my card line-up to get you started:

- The American Express Platinum card – Earn up to 100,000 Membership Rewards points.

- The American Express Aeroplan Reserve card – Earn up to Aeroplan points.

- The American Express Cobalt card – Earn up to 30,000 Membership Rewards points and 5x points on food and drink (this is my main every day credit card).

- The Marriott Bonvoy American Express card – Earn up to 55,000 Marriott Bonvoy points and a free night certificate.

And, for small business owners, even more lucrative rewards await:

- The Business Platinum Card from American Express – Earn up to 120,000 Membership Rewards points.

- The Marriott Bonvoy Business American Express card – Earn up 55,000 Marriott Bonvoy points and a free night certificate.

We’ve got an unbelievable trip lined up for next summer in England, France, Switzerland, and Italy. I’ll share more about that in a future post!

Weekend Reading:

The Globe and Mail’s Erica Alini says Canadians can expect to spend $350,000 to raise a child from birth to 17. I believe it.

Michael Lewis is under fire for taking it easy on Sam Bankman-Fried, the subject of his new book. Here’s where Lewis went wrong.

Why cash ETFs deliver great yields at this moment, but they are no long-term substitutes for classic fixed income funds.

PWL Capital advisors Dan Bortolotti and Justin Bender share a better way to compare bonds and GICs. Excellent analysis.

A must-watch video from Dr. Preet Banerjee on AI and voice cloning technology. Scary stuff!

Many financial advisers only work with wealthy clients. So where are the masses going for help? (hint: contact me).

Mark McGrath with a great explanation of the retirement torpedo – sequence of returns risk.

Jason Heath says these tips can help you avoid financial pain amid the emotions of losing a spouse.

Finally, Rob Carrick asks why is this retiree having so much trouble finding a financial planner to help him draw on his savings tax-efficiently? (subscribers).

Have a great weekend, everyone!

They say life insurance is a product that’s sold, not bought. This decades-old maxim was shamefully brought to light when the Financial Services Regulatory Authority of Ontario (FSRA) looked into troubling sales practices in the life insurance industry.

Troubling, indeed. FSRA examined life insurance agents at three firms – World Financial Group, Greatway Financial Inc., and Experior Financial Inc. – and found the agents broke about 184 rules under the insurance act (that’s all?).

FSRA looked at 24 client files from these agents and found that a Universal Life (UL) insurance product was sold in the majority of cases, despite there being no specific life insurance need:

- In 33% of cases, the customer was sold overfunded UL with the expressed or implicit purpose of helping to fund retirement or grow the value of the client’s estate, yet in 75% of those cases the client did not appear to have a TFSA or RRSP.

- In all these instances the client was a single person in their 20s or early 30s, with no dependents and only modest income.

- In fact, in 70% of the instances the insured stated an annual income of $60,000 or less.

- Further, in 83% of the files reviewed there was no indication that the client had any TFSA or RRSP, and in almost 30% of the cases the client was carrying high interest personal debt, which was not factored into the recommendations.

Also caught in FSRA’s crosshairs was the multi-tiered (pyramid shaped?) business recruitment model prevalent at these firms:

“When compensation for life agents is heavily influenced by the sales of individuals they recruit, this creates the potential to focus on recruiting to greater extent than agent suitability and customer needs analysis.”

FSRA took enforcement action against 65 life insurance agents, and says it may conduct further reviews and follow up with insurers. Good.

Life insurance agents may target those with poor financial literacy skills. The FSRA review showed that permanent insurance is often mis-sold to unsuspecting customers who may not have a need for insurance (let alone life-long insurance), and who may not fully understand the complex product.

For those interested, the team at PWL Capital put together a white paper explaining the ins and outs of permanent insurance that’s well worth the read. They suggest that the motivations to sell insurance as an investment are, in many cases, related to conflicts of interest.

“It is common for insurance agents to earn a commission of 50% to more than 100% of the first year’s policy premium. For large policies, the financial incentive for agents to recommend permanent insurance is substantial.

Importantly, commissions are typically paid to the agent upfront at the time of sale, and that commission only has to be repaid if the policy is cancelled within a two-year window. The agent has minimal financial incentive to provide longterm service and advice to the policyholder, which is starkly misaligned with the fact that many policies are intended as solutions for which the benefit will not be realized for many decades to come.

There is little accountability for an agent who sold an unsuitable permanent policy 10, 20 or 30 years ago.”

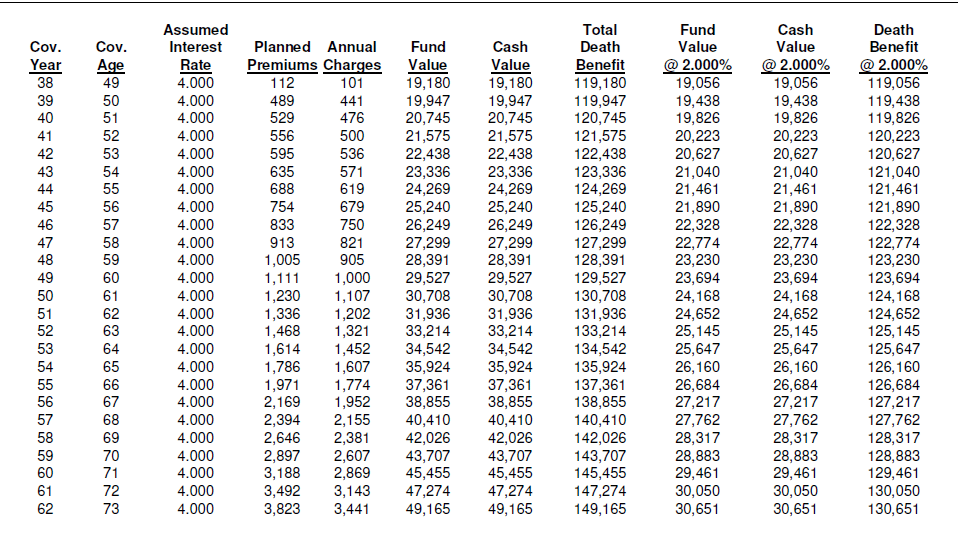

The PWL team also questioned the need for permanent insurance, using a common example of a family cottage that is intended to stay in the family. The idea being to take out a permanent insurance policy to cover any capital gains so that the children can keep the cottage as intended.

While permanent insurance can be used to cover this tax bill, it may not be the best tool. Permanent insurance is expensive.

“A Term-to-100 life insurance policy with a $250,000 death benefit for a 40-year-old healthy male costs about $2,500 per year. If Mom and Dad had simply instead invested their $2,500 annual premiums into low-cost index funds, the resulting investment could likely cover the cottage’s expected tax liability and more. For an investment with contributions identical to the insurance premiums at $2,500 per year until age 90, the required net of tax return to match the death benefit is only 2.6%.”

Were you sold an inappropriate insurance policy?

Financially savvy consumers know that term insurance is cheaper and more plentiful (i.e. you can get more coverage) than permanent insurance. They also know that insurance is insurance – a transfer of risk – and should not be combined with their investments, especially when the alternative is to invest in low cost index funds.

That’s why the phrase “buy term and invest the difference” was coined.

Indeed, the PWL team concluded that a lower level of permanent coverage should never be put in place at the expense of a higher level of required term coverage.

But what if you’re just hearing about this now, and you realize you were sold a permanent insurance policy that is not in your best interest?

I reached out to Jaclyn Cecereu, a financial planner at PWL and co-author of the white paper above, to ask about this exact situation.

She agreed that many people are sold a permanent policy before realizing it may not be ideal for their needs.

When a policyholder owns permanent insurance that isn’t actually necessary for them to have, the cost/benefit of cancelling or unwinding has to be known.

- Cost = what are you giving up if you cancel?

- Benefit = what are you saving if you cancel?

“To do this we look ahead and ignore all past premiums made (i.e. sunk costs are not considered). We review the policyholder’s latest in force illustration to determine whether the policy would be worth buying today assuming there were no coverage in place. The illustration can be requested from the insurance advisor, or directly from the insurance company if there is a desire for discretion. It will include up to date projections of the premium schedule, cost of insurance, cash value, death benefit, dividend scale, etc.”

Ms. Cecereu uses this to figure out the assumed internal rate of return, or in other words, the effective annual after-tax rate of return required on another investment to match the insurance. This is useful to compare existing coverage with other alternatives, in particular the possibility of getting term insurance and investing the difference in planned premiums.

“You are better off with term if, given the outlook today, investing the net premium savings offers better performance than keeping the permanent policy.”

In the early years of owning a permanent policy there is little to no build up of cash value (i.e. equity), so the policyholder might walk away with nothing in return for their initial premiums made. Sort of like paying the mortgage, property tax, and maintenance costs on a home that has not appreciated in value.

Behaviourally, there is an endowment effect bias at play here too which makes it really difficult to walk away. But, it softens the blow to compare sunk costs to the long-term prospect of continuing to incur high unnecessary premiums and potentially giving up higher investment returns.

Some policies have early surrender charges that expire years after a policy is put in force, and these need to be considered too. Instead of cancelling outright, a cash surrender value might buy the policyholder a few years of premium offset. The decision to cancel could be deferred until that cash value runs out, and in the meantime a new term policy can be put in place.

“It is worth noting that if the term insurance application came back rated or denied, you would keep the permanent policy after all.”

Ms. Cecereu goes on to explain that there are situations in which permanent insurance makes more sense than term. This might come up if there is a family cottage with a large, embedded capital gain, where the family wants to guarantee the cottage is inherited by the next generation. Permanent insurance can be used as a tool to cover the eventual tax liability on that transfer. This avoids otherwise having to sell the asset to pay the taxes owing on death.

“We often see it used as a way to mitigate known tax liabilities on death; the date or timeline of the insurance need is unknown, but the amount of the insurance need is (somewhat) known.”

She says they also see permanent insurance used as a way to access cash during the insured’s lifetime, particularly if most other assets are more illiquid, e.g. real estate or private investments.

This is more popular with corporately-owned policies and is often sold as a way to avoid income tax. You can borrow against the overfunded portion of a permanent policy (although this is done at a high unsecured debt rate) to help with liquidity needs.

“In most cases though, there are more efficient avenues to access liquidity, i.e. drawing on an investment portfolio or even borrowing against real assets.”

Final Thoughts

I found myself in a fit of rage reading the FSRA reports on observed practices in the sale of Universal Life insurance. There’s clear harm being done to financial consumers from poorly trained, commission-hungry agents and their (lack of) supervisors.

Term insurance is more appropriate for the vast majority of financial consumers. Don’t even consider Universal Life insurance unless:

- You have a genuine need/purpose for permanent insurance

- You are already maximizing other tax advantaged accounts, such as TFSAs (and/or RRSPs or Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs) as applicable) and you do not need access to your overfunded premiums in the short-to-medium term

- You are prepared to carefully monitor and adjust your policy on an ongoing basis

- You have sufficient means to support increased premiums in the case of future poor investment performance or volatility

Understand that permanent insurance sales are heavily influenced by commissions, and there’s a literal army of life insurance agents out there trying to sell you this stuff (World Financial Group has nearly 11,000 agents in Ontario alone).

Finally, if you have been sold an inappropriate permanent insurance policy, it’s worth looking into the details to see if it makes sense to walk away from the policy in favour of more appropriate term insurance. Understand the trade-offs, though. How much is the cash value? What are the surrender charges?

And, don’t cancel the permanent policy without having term policy in place.