The Most Difficult Account For Investors To Manage

I recently made a bold change to de-risk my portfolio, which now consists of just 35% globally equities and 65% short-term bonds.

This wasn’t in response to tariffs and global trade wars, or my gut feeling about stock markets crashing in the near term.

No, this was a predetermined change in a specific account type to more appropriately align the investments with the expected time horizon of withdrawals.

I’m talking, of course, about our kids’ RESP portfolio!

(I’m still 100% invested in VEQT in my RRSP, LIRA, TFSA, and corporate account – in case you’re wondering how I invest my money).

An RESP is the most difficult account for investors to manage. First of all, the time horizon for contributions and growth is relatively short (17-24 years, in most cases). Second, the withdrawal period is *really* short (typically 4-6 years). And third, you actually *want* to run out of money at the end – meaning you’ve withdrawn all of the funds for your kids’ post-secondary expenses.

Imagine the lifetime of your RRSP being condensed to making contributions between the ages of, say, 43 to 60, and then withdrawing all of the funds from ages 61-65 – intentionally exhausting the account (or risk incurring a tax hit or leaving the funds trapped and unspent).

That’s what it means for parents who are managing RESP funds for their child(ren).

In my experience working with clients and hearing from readers, most parents do not hold an appropriate asset mix in their RESP accounts. Either their investments are too risky (like me, having far too much equity exposure for far too long), or their investments are dreadfully conservative and held predominantly in bank deposits, GICs, and monthly income mutual funds.

Worst of all, there is no strategic thought to shifting this asset mix over time – particularly as their children get into their high school years and beyond.

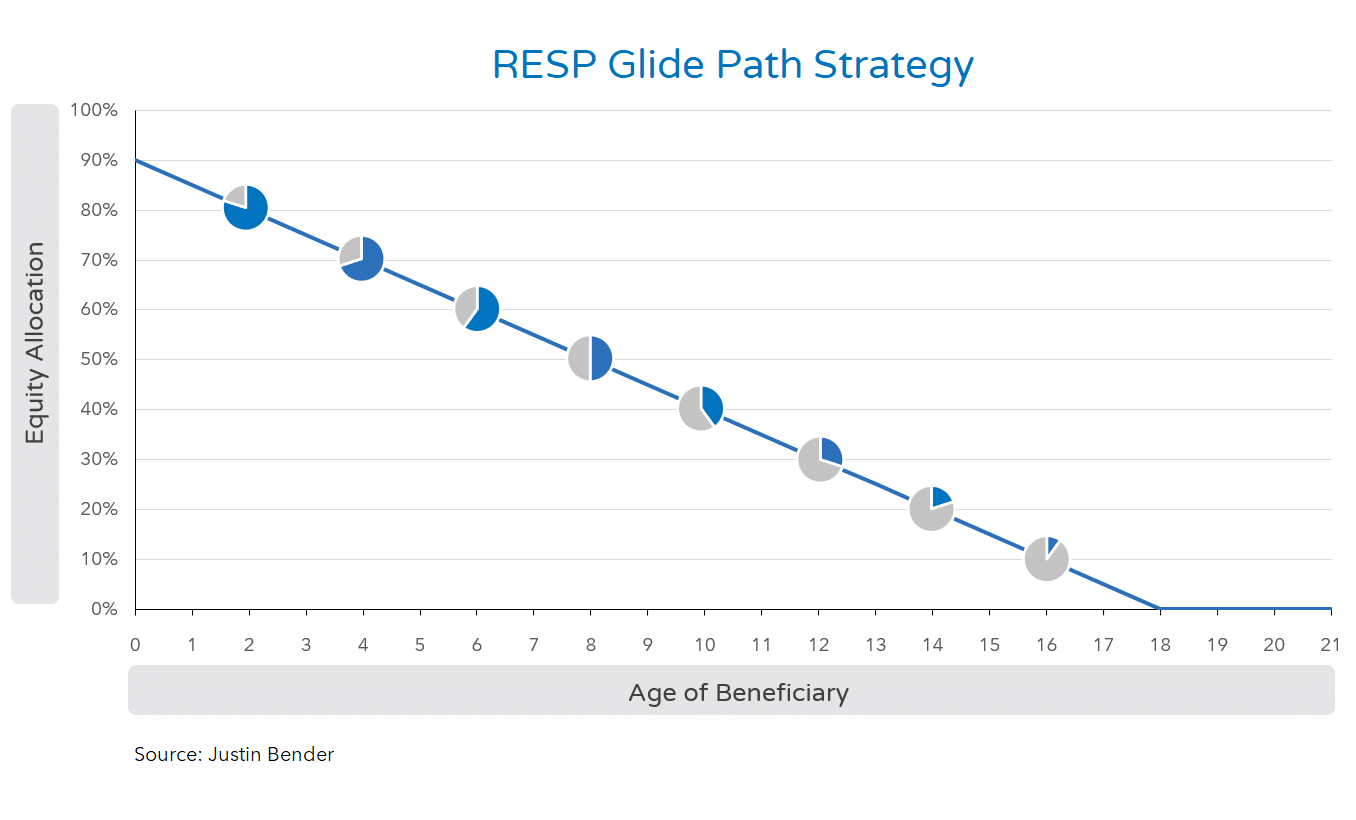

For all of these reasons, I highly recommend following the incredibly useful approach developed by PWL Capital’s Justin Bender for self-directed RESP investors.

The key to managing your RESP portfolio is to have a predetermined glidepath – a rebalancing schedule that you can blindly follow during the contribution and withdrawal years.

In this plan, Justin recommends starting with a portfolio of 90% equities and 10% bonds. Each year you gradually decrease the equity exposure by 5% so that by age 17 you have just 5% in equity and 95% in bonds. At age 18, presumably your child’s first year of post-secondary and of RESP withdrawals, shift the portfolio again to include an allocation to cash or money market funds (25% at 18, 33% at 19, 50% at 20, and 100% at 21).

During the contribution phase, make life easier on yourself and this rebalancing strategy by contributing the entire amount at once in January ($2,500 per child) and adjusting your asset mix for the year at that time.

In a family RESP with multiple children, Justin’s comprehensive article suggests the same approach, but splitting each child’s share of the RESP into different (but similar) ETFs to help parents keep track of each child’s glidepath and share as they age.

For instance, our oldest daughter is in her age 16 year and her share of the RESP account has 25% global equity in VEQT and 75% short-term bonds in VSB (Vanguard).

Our youngest daughter is in her age 13 year and her share of the RESP account has 40% global equity in XEQT and 60% short-term bonds in XSB (iShares).

Finally, follow the rules but feel free to make the strategy your own. For example, you may have noticed that I’m not following the exact recommended age glidepath from Justin’s article, but instead chose the asset mix for a 10 and 13 year old (rather than for a 13 and 16 year old).

I’ll start shifting a portion of the account to cash in two years to help queue-up the first semester’s withdrawal needs for our oldest daughter.

Final Thoughts

RESPs can be a really challenging account type for investors to manage, especially on their own. It’s not as intuitive as, say, your retirement accounts where young parents might be perfectly comfortable investing in 80-100% equities, knowing that their time horizon is long and they want to maximize growth during their working years, but also into and throughout retirement.

To a risk-seeking investor it just doesn’t seem right to hold a 60/40 portfolio for their child who is under the age of 10.

And in your child’s high-school years, reality still might not have set in that they will be withdrawing from this portfolio in the near future. Pair that lack of awareness with a rising stock market and it certainly won’t feel good to take risk off the table and move to short-term bonds and cash. You want to squeeze every drop of return from the market before that happens.

The problem is, as we’ve seen earlier this year, markets can turn negative in a hurry and you could suddenly be faced with a 10-20-30% drop in value at the worst possible time.

In my mind, the RESP is all about maximizing the matching government grants (20% free money!) rather than trying to hit a home run with your investments. Because of the challenging time horizons of your contribution and withdrawal phase, I’d rather err on the side of being a bit too conservative so that I can avoid or minimize regret.

Remember, the phenomenon of loss aversion states that we feel the pain of a loss twice as much as we’d derive pleasure from an equivalent gain.

You got me! Well done with the introduction – led me to read faster than ever, with my heart pounding! haha

Same!! Had to read the first few lines twice over.

So sorry! I should have made this an April Fool’s Day post.

Hi Robb! Thanks for another great post. Just working on switching my kids RESP from managed to self-directed on wealthsimple and following Justin Bender’s approach as well. Just a quick question for you. My kids are still young, 6 months old and 3 y/o. Is there an advantage to using longer term bond ETFs initially then switching over to short-term bond ETFs as they get older and are closer to needing those funds? or does it just make more sense to use short-term bond ETFs the whole time?

Thanks!

Hi Sayla, I think it’s fine to use an aggregate bond ETF (ZAG, VAB, XBB) in the early years. Justin Bender says so himself in the article:

“For the bond ETF, we’ll opt for the Vanguard Canadian Short-Term Bond Index ETF (VSB). This ETF invests in Canadian government and corporate bonds with maturities ranging from 1 to 5 years.

[Note: You could also consider a broad market Canadian bond ETF, like the Vanguard Canadian Aggregate Bond Index ETF (VAB) – just remember to gradually shift the holding to VSB as your child gets older].”

Great article. I have 5 grandchildren – 13, 13, 10 yr old in on RESP and 10,7 yr old in another. Started investing in the year they were born.

Wth the first one, I currently have 30% in laddered GICs – some at 4.4-4.8 % maturing in 4 years.

Other holdings FTS, ENB, TD, and varied ETFS – XIU, XAW, VDY.

I am interesting in your thoughts on this compared to short term bond funds which seem to be a bit lower in interest rate. Are the GIC and bond rates similar right now?

Hi Bruce, good for you for contributing to your grandchildren’s education – very generous and I’m sure much appreciated by the parents!

I can’t argue with the laddered GIC approach, as those rates are well above short-term bond yields and money market funds.

The problem (I think) will be upon maturity of those higher rated GICs.

I like the simplicity and flexibility of the 2-3 fund approach (VEQT + VSB, and then eventually CASH).

One advanced planning trick about managing the RESP is if your RESP exceeds the size of your kids need, you can sock some of that money into your kids TFSA (a la Aaron Hector’s withdrawal strategies for 100k and 200k RESPs, linked here: https://www.fpcollective.ca/author/aaron/ )

If that is part of the plan, then the time horizon for those monies becomes much longer and this you can continue to take more equity risk even as the withdrawal date approaches. It is fine to pull out when your investments are down 30% if you are simply moving those investments to another tax shelter. But if you are actually paying for school with the majority of the money, then you are correct that you need to reduce risk. And as you correctly mentioned, short term bonds (or GICs) are appropriate. An aggregate bond fund likely isn’t suitable.

You one-percenters and your advanced planning techniques 😉

Good comment.

Another perspective is that unused RESP monies can be collapsed back to the owners account – in our case this would be into our investment accounts. Yes there is taxation to worry about, and as I understand this could be partially mitigated if you can move some funds into your RRSP (if you have room).

With this perspective in mind then a long term investment horizon and investment risk could be considered. Right?

I’m interested in hearing opinions on this approach – pros and cons.

Disclosure – I stayed 90% equities and after the recent ~4 years of one child’s post secondary schooling I have almost the same amount in the family RESP. They stayed at home and daily commuted to local Uni. Second child is starting post secondary this fall with same approach.

Thank you for this! I’ve also found your other articles about RESPs and Justin Bender’s strategy to be helpful.

One thing I have not understood is why choose a short term bond ETF? Why is something like VSB preferred to the likes of VAB or ZAG in this situation?

Thank you!

Hi Caitlin, it’s all about matching a bond’s average “duration” to your expected liabilities (spending of the funds).

Aggregate bonds like ZAG might have a duration of 8-12 years, so they’re perfectly suitable during the early stages of the RESP.

But later on you’d want to switch to a shorter duration bond (3-5 years) as you get closer to needing those funds.

Shorter-term bonds won’t fluctuate as widely when interest rates move up and down, so they’re more steady when you just want some safe and reliable income as your children enter high school age.

Thanks! That makes sense.

Robb, what do you think of the strategy of doing a lump sum payment into the RRSP in year 1 for the total lifetime limit and forgoing the government grant since compounding that initial lump sum over 18 years will likely lead to a better outcome than getting the grant every year and investing at a slower pace?

Hi Rohit, so this has been modelled out a few times and, while dependent on investment returns, the optimal funding of an RESP is to do the following:

– contribute $16,500 in year one

– contribute $2,500 per year for the next 13.4 years

The initial deposit gets the unmatched $14k into the RESP right away for longer compounding, plus the additional $2,500 maxes out the matching grant for year one.

This way you get all of the grants, and front load the unmatched contributions right away.

One other scenario that looked good was depositing $42,500 in year one, and then $2,500 per year for three years. This gives you $2,000 in matching grants while front loading most of the other contributions in year one.

Putting the entire $50k in right away was not optimal, and the outcome is highly dependent on future returns.

Whereas getting some or all of the grants acts as a hedge against poor market returns.

I was shocked too. Thinking to myself, wow he did it again! (Re-accounting the time you switched from dividends to one ticket). Good post!

Something which deserves some thought is what I believe is called contingent RESP account owner. As I understand it, if I and my wife pass away, without a contingent owner for the RESP account, then the RESP gets folded into my estate, and then .loses the advantage of growing tax-free. Some banks (e.g. BMO) have contingent owners, and some do not as in my case with RBC. I am told I then need to have my lawyer amend our wills to stipulate that XYZ person is the contingent owner. This is something that does not get a lot of financial-media attention, but hoping you can review my comments for accuracy?