The Canadian Financial Summit is back for its seventh year and I’m really excited about this year’s line-up of speakers. This year’s conference takes place from October 18th to 21st. You can grab your free ticket here.

A reminder for those of you new to the Summit – it’s a virtual (and free!) personal finance conference featuring nearly 50 Canadian money experts and a wide range of topics, such as:

- How to plan your own retirement at any age

- The Pension Paradox: Lump Sum vs Cash for Life (<– That’s me!)

- How to save money on taxes by optimizing your RRSP to RRIF transition

- Plan your personalized combination of a DIY portfolio alongside an annuity for a customized stream of retirement asset growth + monthly income.

- How to maximize the new FHSA (First Time Home Savings Account)

- How to adjust for high interest rates in your portfolio and day-to-day life

- How to efficiently transition your investing nest egg to a steady stream of retirement income

- What Canadian real estate investments looks like in 2023

- How to deal with inflation on your bills and in your investment portfolio

- The best Canadian personal finance books of all time!

- When to take your OAS and CPP

- Travel for free with Canada’s loyalty rewards programs

Besides hearing your favourite personal finance blogger discuss the ins and outs of defined benefit and defined contribution pensions, you’ll also hear from Globe & Mail columnist Rob Carrick, advice-only planner Jason Heath, former long-time Toronto Star columnist Ellen Roseman, My Own Advisor blogger Mark Seed, and so many more.

But I think the highlight of the conference will be Dr. Preet Banerjee presenting his research on the value of financial advice to Canadian households. For too long, the financial advice industry has tried to quantify the value with industry funded studies proclaiming something like advised households are 2.73x wealthier than non-advised households. Newsflash: wealthy people seek financial advice. The advice may be valuable, but it didn’t make them wealthy in the first place.

I got a sneak peek at Dr. Banerjee’s research at a recent conference and while I won’t spoil the presentation I will say the most interesting finding was that households with a financial plan (regardless of their primary channel of advice) are better off than households without a financial plan. Interesting!

Get your free ticket to the Canadian Financial Summit here and check out the amazing line-up of speakers over this three-day virtual conference.

This Week’s Recap:

I had the pleasure of attending the IAFP Symposium in Edmonton last week and was invited to speak on a panel about using online marketing to grow your advisory business. Having written here (and around the web) for nearly 15 years, I figured I had something useful to say on the topic. Here’s a nice recap of the panel discussion.

This week I wrote about singles and the challenges they face when it comes to home ownership.

Last week I explained how to trick your lizard brain into saving more money.

Next week I’ll be a guest on the Money Feels podcast with Alyssa Davies and Bridget Casey. Watch (listen?) for that on Thursday.

Weekend Reading:

Advice-only financial planner Jason Evans looks at three retirement planning obstacles to overcome.

Here’s Tim Cestnick with two smart RRIF strategies to consider as part of your estate planning (subs).

Why clients with large RRSPs and RRIFs might benefit from earlier withdrawals to help smooth out income over their lifetime.

Rob Carrick shares a guide to starting CPP and OAS benefits when you retire, and says – yes, it’s on you to do that.

This podcast is worth your time: The psychology of retirement spending and prioritizing peace of mind with Christine Benz.

Of Dollars and Data blogger Nick Maggiulli on the never ending “then”:

“The problem with living in the future is that you tend to overlook the present. You can’t fully enjoy something when you are always thinking about what’s next.”

Morgan Housel says that money can bring happiness but it also brings complexity, and complexity can quickly lead to unhappiness.

The Plain Bagel YouTube channel explains the Canadian housing crisis:

PWL Capital’s Ben Felix answers a question on many people’s minds: why invest in stocks when you can get better interest with HISA?

Here are 12 must-see charts and themes that tell the current story in markets and investing.

A Wealth of Common Sense blogger Ben Carlson explains how investors can outperform the pros.

Is that $5 coffee actually free? How TikTok’s ‘girl math’ trend is changing the online money conversation.

Get yourself a Globe & Mail subscription just for Fred Vettese’s excellent Charting Retirement series. His latest chart looks at the best place to retire in Canada, income-wise (subs). Let’s just say it gets better as you go east to west.

Have a great weekend, everyone!

Canada is in a full blown housing crisis. While much of the housing conversation centres around sky high prices in Toronto and Vancouver, affordability issues stretch across the entire country. The average home price in Canada was $650,140 as of August 2023. This is especially problematic for single Canadians.

Canada’s single population has increased steadily since 2000. According to Statista, there were more than 18 million singles living in Canada in 2022 (9.67M men and 8.60M women).

What’s a single with homeownership aspirations to do? It’s a difficult question without a lot of satisfying answers.

- Earn higher than average income consistently throughout your career

- Curb expectations for how much house you can realistically afford

- Be willing to sell the home to help fund retirement spending

- Find a partner with whom to share expenses

Easier said than done.

Let’s take a closer look at a real life situation. Katherine is 33-year-old single living in Calgary, Alta. She earns $80,000 per year working for a mid-sized company, with no pension and no employer matching savings plan. She plans to retire at age 65.

Katherine loves her apartment – it’s close to work and to all of her favourite amenities. Best of all, she pays just $1,600 per month in rent as a long-time tenant. Her total after-tax spending is $54,000 per year.

Despite her current situation, Katherine does feel pressure (FOMO) to buy a home and wants to know if home ownership is possible without derailing her finances. She opened a First Home Savings Account (FHSA) this year and plans to fund it with $8,000 before year-end. She’ll continue to prioritize the FHSA for the next four years, and aims to buy a home in 2028.

Price point matters, and Katherine is looking at condos in her area that are currently listed for $400,000. She thinks it would be realistic to budget $450,000 for such a condo in 2028. She’d prefer to put 20% down ($90k) to avoid CMHC premiums.

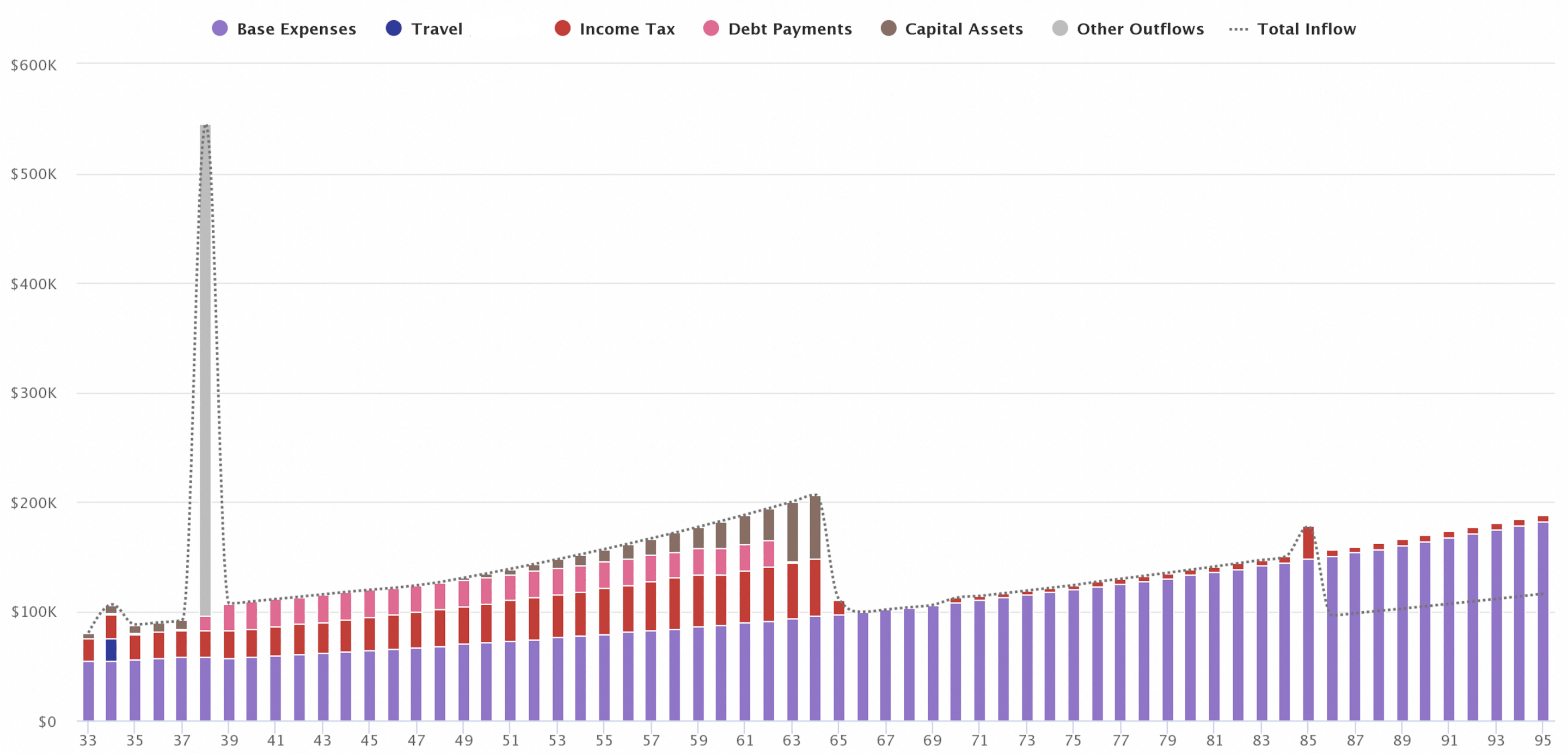

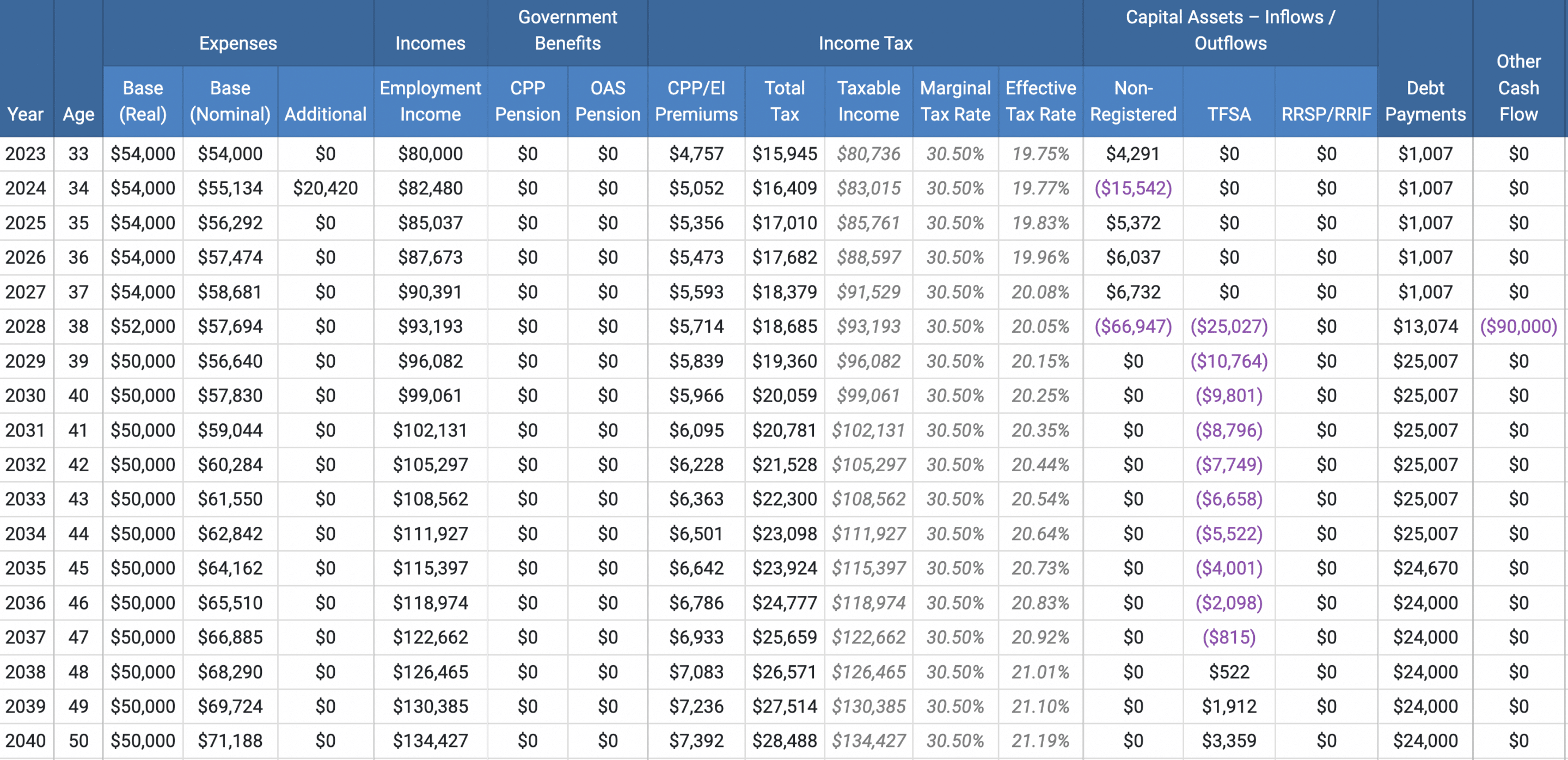

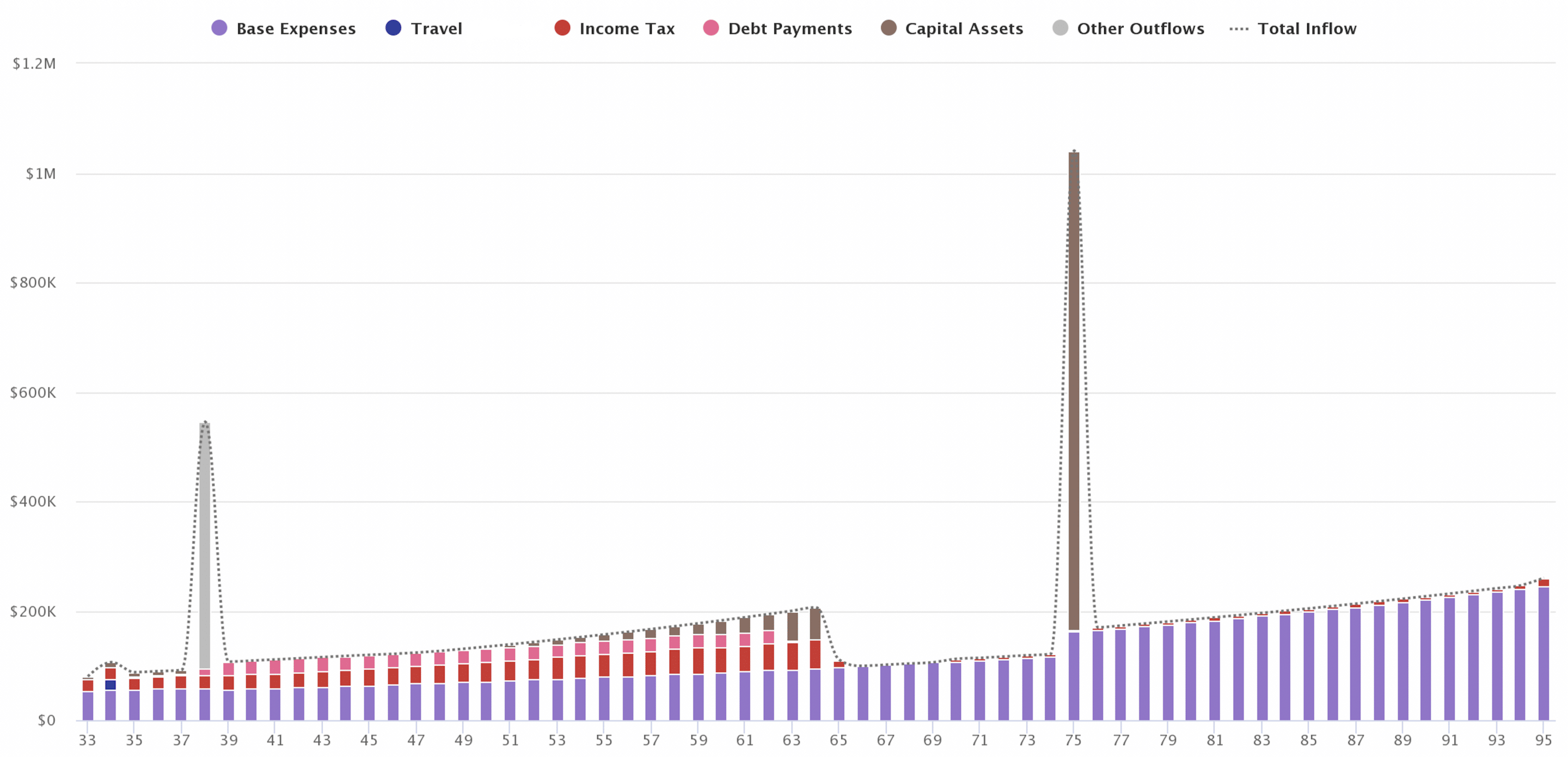

The numbers start to paint a picture as we model this out over Katherine’s lifetime.

First, we need to know how Katherine’s expenses will change when she becomes a home owner. We’d eliminate the rent expense of $1,600 per month ($19,200 per year), but then we must add phantom home ownership costs like house insurance ($2k), property taxes ($4.5k) and maintenance ($4.5k). So, Katherine’s after-tax spending goes from $54,000 down to $45,800.

But, she also expects to buy a new car around that time, so we should budget an additional $350 per month ($4,200 per year). That brings the after-tax spending back up to $50,000.

We also need to factor in the mortgage, which will come to $2,000 per month ($24,000 per year). At an average borrowing rate of 4.4% over the life of the mortgage, the home will be fully paid off by 2053 (25 years). That aligns with Katherine’s desire to enter retirement mortgage-free.

Let’s stop and think about the implications of buying a home. A straight “rent versus mortgage” comparison shows that Katherine would only need to increase her budget by $400 per month and she can happily own her own home instead of flushing rent money down the toilet.

A savvier evaluation shows that the total cost of home ownership is closer to $2,916 per month (mortgage + property taxes, insurance, maintenance) – an increase of more than $1,300 per month. Katherine is now spending $74,000 per year to live the same lifestyle as a home owner.

The implications here are massive. Remember, Katherine does not have a workplace pension or savings plan. She’s on her own to contribute to her retirement accounts, and the focus for the next five years will be on funding the FHSA so she can buy a home in 2028. She’s no longer contributing to her RRSP or TFSA.

Fast forward to 2029 (post home purchase) and Katherine is adjusting to her new reality of spending $74,000 per year. The painful reality is that Katherine will be in a cash flow deficit for nine years, where she’ll have to withdraw from existing savings to meet all of her spending needs. This assumes both spending and income increase by 2.1% annually.

Katherine will need to ramp-up her savings big-time from age 50 to 64. Indeed, it’s possible for her to save and invest her way to about $780,000 across her RRSP and TFSA accounts by the time she turns 65. The house is also paid off, and is now worth nearly $800,000.

Is it possible for Katherine to retire and maintain her standard of living while remaining in her house? Unlikely.

In this scenario, Katherine runs out of money at age 85 and would need to unlock her home equity through an outright sale, a downsize (but she is already in a condo), or a reverse mortgage to maintain her standard of living.

That, or reduce her spending to $45,000 per year (a 10% reduction in today’s dollars) from age 65 onward. Not ideal, but certainly possible.

It might be wise to sell the house at age 75 and rent for the remainder of her life. Doing so allows Katherine to spend $67,415 per year in today’s dollars, which would be enough to pay for rent and still maintain the same (or better) quality of life to age 95.

Final Thoughts

This is just one example of a single woman buying a modest home in a major Canadian city by age 38. Katherine has above average income and lives in a city where condos can still be purchased for less than $500,000.

Still, things are tight. Katherine won’t have the cash flow to contribute to her retirement savings for more than a decade while she saves up a downpayment and then adjusts to the new and expensive reality of carrying a mortgage and other phantom costs.

She starts saving again (modestly) by age 48, but won’t even get her savings rate up to 10% of gross income until age 58. That’s a lot of heavy lifting to do in her final working years to build up an appropriate amount of retirement savings.

And, this assumes everything goes according to plan. Income continues to increase with inflation, and spending remains constant (in today’s dollars) throughout her working career. In reality, she may have multiple vehicle purchases, planned home renovations, unplanned home and auto repairs, income interruption of some kind, a bucket list vacation expense, etc.

Of course, the opposite is also true. It’s more likely that income increases by at least inflation + 1% each year (on average between merit, cost of living, and promotions over time). It’s also possible that Katherine finds a partner with whom to share expenses. This would significantly change Katherine’s cash flow throughout her working career and into retirement.

For singles in higher cost of living areas, home ownership is likely out of reach for all but the top 10-20% of income earners.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. Renting has a certain stigma, at least here in Canada, but more and more of my clients across Canada are realizing that “drive until you qualify” doesn’t lead to a higher quality of life. Indeed, a longer commute in a suburb far away from the vibrance and liveliness of the city may not bring you long-term joy (home ownership be damned).

One client quickly realized this and chose to sell the suburban home he bought just a year ago and move back to renting an apartment in the exact neighbourhood he wanted nearby his work and social life.

In any case, the home ownership dream for single Canadians is on life support and will require more careful analysis (case-by-case) in higher cost of living centres. Consider the trade-offs and whether they’re worth it to pursue your dream of buying a home as a single.

Humans aren’t wired to make rational decisions. Our lizard brain, responsible for satisfying all of our primitive survival needs – including safety, hunger and feeling as good as possible at all times – sabotages our behaviour every day. And it can sabotage our bottom line, too.

Lizard brain makes us do the same things – good or bad – over and over again so it’s the king of bad habits. If you’re chronically late to make payments on your credit card or always forget to transfer money to your savings account, your lizard brain could be to blame. That said, you can counter its reluctance to change its well-worn ways of doing things by automating your personal finances as much as possible. This blocks the lizard from making poor spend-or-save decisions.

Tricking Your Lizard Brain

First, make an unbreakable habit of paying yourself first. This is a powerful strategy that treats your savings like a high-priority fixed expense that automatically gets whisked away from your bank account on or around payday. The idea is that you’re more likely to stick to your plan when you make savings automatic.

Imagine if the government, instead of deducting federal and provincial tax from each paycheque, simply asked employees to send in a lump-sum payment at the end of the year. There’s a reason why government automatically deducts taxes from your paycheque – to make sure it gets paid!

So follow suit and pay yourself first through automatic contributions to your RRSP, TFSA, RESP or other savings vehicles and trick your lizard brain into thinking that money was never there to begin with.

Another tricky thing about the lizard brain is that it makes us act emotionally and live each day as if it were our last. Think of it as the original proponent of YOLO.

That impulse shows up in many of us when we’re shopping and can be exacerbated if we’re paying with plastic. Research shows that using a credit card activates the rewards centre of our brains, causing us to spend more. There’s also the pain of paying – we tend to feel more pain when we spend cash than we do when we use a card; therefore we’re less likely to part with a dollar bill.

Credit-card rewards can be enticing, however not at the expense of missing a payment and turning your 2% reward into a 19% penalty.

So what’s the rule? Use a credit card for recurring monthly payments such as your cellphone bill and Netflix subscription. The steady activity helps build your credit rating. Then arrange to have the full balance automatically debited from your account each month. Use cash for groceries, gas and entertainment – all the things the lizard badly wants – that you can’t automate and need to stay in control of.

Also be aware that lizard brain can be baited. Marketers are well practiced at using psychology to lure that part of our brain into making irrational decisions, constantly tempting us to spend money.

Use what behavioural experts call a commitment device – something you do today that restricts bad behaviour in the future. Ubiquitous examples include freezing your credit cards inside a block of ice to avoid an impulsive shopping binge, or not bringing junk food into the house when you know you’ll go on a late-night pantry raid.

A weekly meal plan can be a commitment device if it prevents you from getting takeout after work. See, this is easy!

Final thoughts

As for me, my lizard brain springs to life whenever my wallet is flush with cash. Apparently I turn into Mr. Generosity, over-tipping at restaurants, buying drinks for friends, giving in to my kids’ impulsive requests. It’s really quite pathetic.

My wife smartly suggested I stop carrying cash and simply use my debit or credit card when we go out. Hey, that’s a great commitment device, honey! But then when I pointed out all the money she could save by removing the Lululemon app from her phone, her cold stare nearly sent my lizard brain back to the ice age!