Weekend Reading: Market Volatility Edition

The last quarter of 2018 was a miserable time for investors. The S&P 500 had reached an all-time high on September 21, 2018. Three months later it had fallen nearly 13 percent – erasing 18 months of gains along the way. The TSX also fell more than 13 percent. Panic ensued, with many pundits predicting the beginning of the next stock market crash.

That didn’t happen. Instead, the S&P 500 proceeded to climb to new all-time highs. At market close on Friday, the U.S. market had gained an incredible 27.72 percent since its December 21st low. Not to be outdone, the TSX gained a healthy 24.15 percent in that time.

Welcome to market volatility.

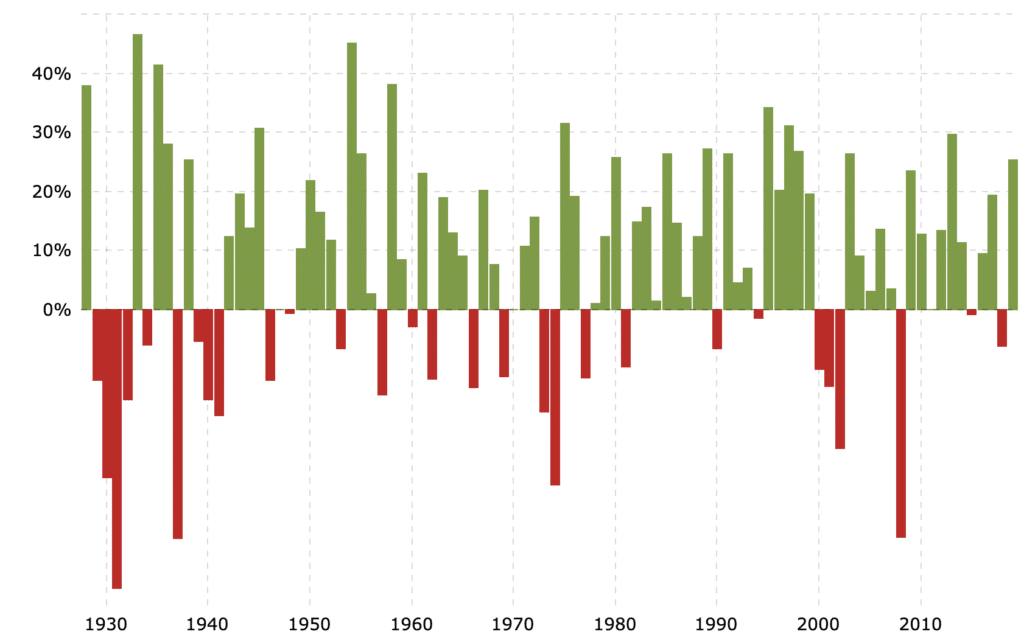

Most reasonable investors, depending on the make-up of their portfolio, can expect to earn market returns of 6-10 percent over the long term. But the dispersion of those expected returns can vary wildly, from 47 percent losses (1931) to 47 percent gains (1933) and everything in between.

Exactly how volatile is the stock market? From 1928 to 2019 (91 years), the S&P 500 posted annual returns of between 6 and 10 percent exactly six times (1959, 1965, 1968, 1993, 2004, 2016).

The market lost ground in 29 of those 91 years (roughly one-third of the time), with six of those years posting losses of 20 percent or more.

Investors should accept this volatility to capture the market risk premium – the difference between the expected return on a market portfolio and the risk-free rate – over the long term.

But, behaviourally, we’re prone to panic when markets fall and to feel elated when markets rise. We know this behaviour is to our detriment, yet we do it time and time again. Markets fall, investors sell. Markets rise, investors buy back in.

The winning investor is the one with the fortitude to stay invested during turbulent times. Yes, markets can fall. They tend to do so one-third of the time. This is fully expected. But panic-selling at the bottom also tends to miss the inevitable recovery, which often comes quickly.

How do we curb our bad investing behaviour? We start with an appropriate asset mix of stocks and bonds. How do you know what’s appropriate? Take a close look at the above chart and decide how much money you’d be prepared to lose in a given year.

Adding bonds smooths out market volatility and delivers a tighter dispersion of returns.

The biggest one-year loss posted by a portfolio with 40 percent stocks and 60 percent bonds has been -11.82 percent. The classic balanced portfolio of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds lost 19.61 percent in its worst year, while an all-equity global portfolio has posted a one-year loss of -34.85 percent*.

*Source: CPM Model ETF Portfolios

Another trick is to simplify your portfolio to the point where you can ignore it for long periods of time. That’s why Rip Van Winkle would have made a great investor. Automate contributions and rebalancing whenever possible. This can be done through a robo-advisor or, for DIY investors, an asset allocation ETF.

That’s exactly where I’m at with my all-in-one investing solution (VEQT). I didn’t even realize markets were down last quarter until I heard it on a podcast in mid-December.

Finally, making smaller, more frequent contributions helps eliminate the desire to hold off until things “settle down” or “feel safer”. Automate and ignore.

This Week’s Recap:

Speaking of bad behaviour, this week I wrote about how to trick your lizard brain into saving more money.

Over on Young & Thrifty I went back to my dividend roots and looked at the pros and cons of a dividend investing strategy.

It’s my last official day of work next Friday! I’ll continue to keep you posted on my transition to full-time entrepreneur. My life insurance policy was approved and is now in place. That means an overlap in coverage and twice the death benefit if I die in December. My wife is weighing her options.

Next up is a look at my pension, and the decision whether to leave it in the plan and take a deferred pension at 55 (or older), or transfer the commuted value of the pension into a LIRA. I have a good idea what I’d like to do, but I’m waiting for the official documents from the pension board before I make my decision.

Promo of the Week:

I’ve fielded quite a few questions from retirees about moving their portfolio to Wealthsimple to save on fees and to help with automating retirement income withdrawals. First, I send them to this excellent case study on using Wealthsimple in retirement.

Transferring to Wealthsimple is about as easy as it gets. I know because I’ve helped my wife transfer her RRSP to Wealthsimple and it was a breeze.

Finally, to open a Wealthsimple account, use this referral link and you’ll get your first $10,000 managed free.

Weekend Reading:

The federal government announced the new TFSA contribution limit in 2020 will remain the same as 2019 at $6,000. That brings the total contribution limit to $69,500 for an eligible Canadian who has never contributed to his or her TFSA.

I’m sure many of you have seen the Laurentian Bank’s digital arm (LBC) offering a 3.3 percent high interest savings account. Rob Carrick asks if you should jump on this rate, while cautioning readers that this rate is highly unlikely to remain this high, despite what the bank says. We’ve seen this movie before from EQ Bank, which entered the market at 3 percent before eventually settling in at a still reasonable 2.3 percent.

Did you shop on Black Friday? Here’s why lawmakers in France are trying to ban Black Friday to help stop waste.

Why the pain of a failed investment can be the best teacher of all:

Those who have never experienced large market declines are at a distinct disadvantage to those who have. Many investors today don’t even remember the near-collapse in 2008, the bear market of 2000 to 2002 or the white-knuckle abyss of 1987.

A Wealth of Common Sense blogger Ben Carlson explains why market all-time highs are both scary and normal.

Carlson and his Animal Spirits podcasting cohort (Michael Batnick) debate whether day care is the next student loan crisis:

As people live longer than ever, there’s danger in counting on an inheritance to fund retirement.

Rob Carrick has a message to the 42 percent of credit-card holders who do not pay their balance in full every month: Stop using your card and switch to debit.

Dale Roberts explains why you don’t have to be the perfect investor trying to build the perfect portfolio. It’s more than OK to be a great investor.

On the My Own Advisor blog, Mark Seed and Steve Bridge debate whether the 4 percent safe withdrawal rate still makes sense.

Finally, credit expert Richard Moxley explains how your cell phone bill can keep you from getting the best mortgage rate.

Have a great weekend, everyone!

Rob – I encountered a similar situation with a defined benefit (DB) pension about 5 years ago. Approximately 6 months after I resigned from public sector job, I decided to transfer out the commuted value into a LIRA plus lump sum payment. I thought self-investing with some risk outweighed minimal risk with defined pension benefits. I also took a job in the private sector and did not anticipate returning to public sector where I could rejoin or transfer pension to another defined benefit plan.

2 years later, I was recruited for a senior position back in public sector with big salary increase. I ended up taking the job, and was back in a DB pension plan. My previous DB pension service and contributions were already transferred out to LIRA, so couldn’t bring them back in. I estimate that had I left them in place and transferred them into my new pension, the value of that past service would have increased significantly based on new higher salary factored into the best five year average salary used to calculate pension benefits. The investments in LIRA have done well based on market returns over last few years, but in hindsight I should have waited for a little while before making the decision to transfer out previous pension and close the door to opportunity for future pension transfer.

So my suggestion to you based on my own experience – defer your decision on whether to transfer out to LIRA for at least a year or two. A lot can change in that time period, or you may be certain at that point that you will not be returning to public sector and DB plan. The downside of waiting should be minimal over a year or two, i) opportunity cost on earnings (or losses) of that commuted value in your LIRA; and, ii) potential + or – changes in commuted value over that time period. But in my opinion and experience the upside in maintaining that pension service and contributions for possible transfer into another DB plan for a short time is worthwhile, even if returning to employment with a DB plan seems unlikely at this point in time.

All the best,

Andrew