Reframing The RRSP Advantage

I’ve read a lot of bad takes on RRSP contributions and tax rates over the years. One that stands out is the argument that you should avoid RRSP contributions entirely, and focus instead on investing in your TFSA and (gasp) your non-registered account. This idea tends to come from wealthy retired folks who are upset that their minimum mandatory RRIF withdrawals lead to higher taxes and potential OAS clawbacks. They also seem to forget about the tax deduction generated from their RRSP contributions and the tax-sheltered growth they enjoyed for many years leading up to retirement.

I’m hoping to dispel the notion of an RRSP disadvantage by reframing the way we think about RRSP contributions, RRIF withdrawals, and tax rates. Here’s what I’m thinking:

Most reasonable RRSP versus TFSA comparisons say that it’s best for high income earners to prioritize their RRSP contributions first, while lower income earners should prioritize their TFSA contributions first.

The advantage goes to the RRSP when you can contribute at a higher marginal tax rate and then withdraw at a lower marginal tax rate, while the advantage goes to the TFSA when you contribute at a lower rate and withdraw (tax free) at a higher rate.

If your tax rate in your contribution years is the same as in your withdrawal years then there’s no advantage to prioritizing either account. They’re mirror images of each other.

Related: The next tax bracket myth

This comparison focuses on marginal tax rates. But is this the correct way to frame the discussion?

Marginal Tax Rate vs. Average Tax Rate

Isn’t it fair to say that an RRSP contribution always gives the contributor a tax deduction based on their top marginal tax rate (assuming the deduction is claimed that year)?

But when you look at retirement withdrawals, shouldn’t we focus on the average tax rate and not the marginal tax rate?

An example is Mr. Jones, an Alberta resident with a salary of $97,000 – giving him a marginal tax rate of 30.50% and an average tax rate of 23.59%

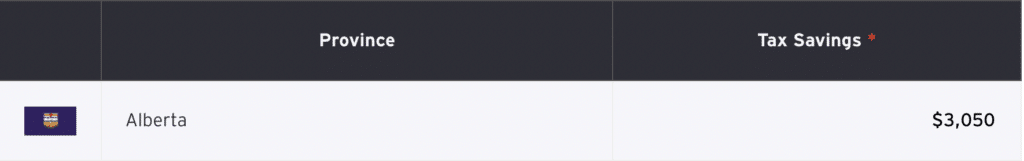

If Mr. Jones contributes $10,000 to his RRSP he will reduce his taxable income to $87,000 and get tax relief of $3,050 ($10,000 x 30.5%).

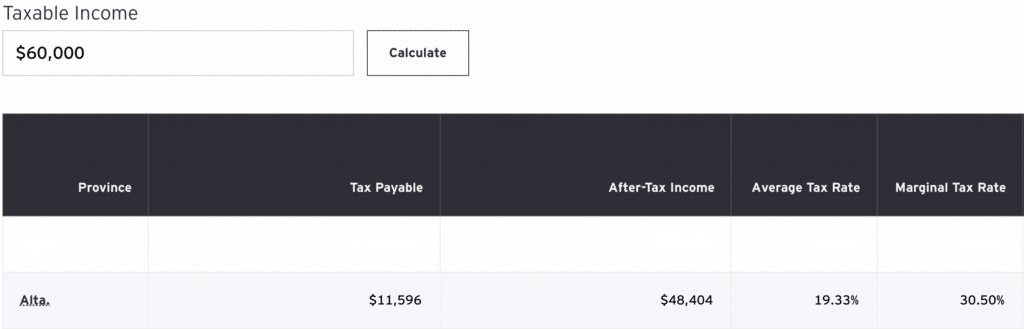

Fast forward to retirement, where Mr. Jones has taxable income of $60,000 from various income sources, including a defined benefit pension, CPP, OAS, and his $10,000 minimum mandatory RRIF withdrawal.

The range of income in each tax bracket can be quite broad. With $60,000 in taxable income, Mr. Jones is still at a 30.5% marginal tax rate, but his average tax rate is just 19.33%. That’s right, he pays just $11,596 in taxes for the year.

Conventional thinking about RRSPs and marginal tax rates would tell us that Mr. Jones should be indifferent about contributing to an RRSP in his working years because he’ll end up in the same marginal tax bracket in retirement.

But when we consider all of our retirement income sources, why do we treat the RRSP/RRIF withdrawals as the last dollars of income taken (at the top marginal rate) instead of, say, income from CPP or OAS or from a defined benefit pension? Why would Mr. Jones’ $10,000 RRIF withdrawal be taxed at 30.5% when it’s his average tax rate that matters?

Put another way, let’s say Mr. Jones asked his financial institution to withhold 30% tax on his $10,000 RRIF withdrawal. Wouldn’t he get a tax refund after filing his taxes revealed an average tax rate of 19.33% (assuming other income sources were taxed appropriately)?

What if we assume zero withholding taxes were taken from the defined benefit pension, CPP, OAS, and minimum RRIF withdrawal (of $10,000)? This taxpayer simply owes $11,596 at tax time (ignoring other deductions for simplicity). Why would we think the RRIF withdrawal is taxed at 30.5%? And, if we did, then which income stream is counted first and gets the basic personal amount treatment (yay, my CPP and OAS are tax-free!)?

The point is, all of your income streams converge into one pile of income and they’re taxed at your average tax rate.

Finally, I get that RRSP/RRIF withdrawals are often subjective – as in you can choose when and how much to take prior to RRIF conversion. You can also take more than the minimum from your RRIF, in which case your marginal tax rate may come into play when considering additional withdrawals.

But a lot of the pushback against contributing to your RRSP in the first place seems to come from high income retirees who argue that the minimum RRIF withdrawals are causing high tax rates and OAS clawbacks. So it seems like they’re not taking any more than the mandatory minimum – which makes the RRIF withdrawal a fixed amount similar to CPP, OAS, and the defined benefit pension.

Final Thoughts

I get there is a lot of nuance to this discussion, but my basic argument boils down to this:

It’s helpful to think about your RRSP contribution as always receiving a tax deduction at your top marginal rate, and to think about your RRSP/RRIF withdrawals as being taxed at your average tax rate (especially if you’re just taking minimum RRIF withdrawals). This strengthens the advantage of contributing to your RRSP and hopefully dispels any bad notions about avoiding RRSPs due to tax implications.

PS – this doesn’t even touch on the other RRSP advantages such as qualifying for additional Canada Child Benefit for parents with young children by lowering their net family income, or the ability for retirees to split RRIF withdrawal income after age 65 to save on taxes.

Bottom line: While there are situations when contributing to an RRSP is not a good idea (such as for low income earners who may qualify for GIS), most Canadians should be taking advantage of their RRSP contribution room for immediate tax relief, long-term tax-sheltered growth, and flexible retirement withdrawals at their average tax rate.

You don’t do it that way because it’s not helpful in decision-making. You can’t opt to do something else with your CPP or OAS payments, so it doesn’t make sense to consider those the marginal income. The RRSP though you have the choice of investing in a TFSA or keeping in a non-registered instead, and when making that choice it’s the marginal tax rate that’s useful.

If you say “hey, the average tax rate in retirement is 16%, which is lower than the 30% when you contribute, so the RRSP has a huge advantage over the TFSA, go nuts!” But then if you actually compare the two scenarios they come out the same, then the shortcut isn’t helping you in the analysis the way you may think — so using marginal rates (as we do) would be the correct way to help make the decision.

Similarly, we don’t hand-wave credit card debt by saying well, it’s $10,000 at 20%, but with my $500,000 mortgage at 2.5% my average debt only costs 2.6%, so no need to worry yet about a little more.

Potato is correct that it’s the marginal tax rate in retirement that matters when you’re deciding where to contribute. Once the RRSP contribution is made, then Robb’s arguments about average tax rates are relevant in certain retirement drawdown decisions.

That said, Robb is spot on about the rule of thumb to use RRSPs when income is high and TFSAs when income is low. He’s also right about all the nonsense we read about people not liking RRSPs when it comes to paying taxes in retirement. An article I saw recently (that might have been Robb’s inspiration for this article) contained some moaning about taxes on RRSP withdrawals by someone with over 8 million dollars who apparently spent a lifetime spending very little. This person’s situation is relevant to almost nobody.

Potato is correct. Apple’s to Apple’s comparison requires you compare marginal tax rates. Realize that marginal applies only to the increased rrsp contribution but if comparing to average tax in retirement the increase affects your entire income.

I guess I’ve been thinking about it from the perspective of the retiree who’s complaining about getting taxed on the RRIF withdrawals. The contribution decision was made long ago.

They’re only taking minimum RRIF withdrawals, so they are in a sense fixed just like CPP, OAS, and the DBP (agreed that a decision to take more out of the RRIF would be at the marginal rate).

That one was a classic of allowing the “tax tail wag the dog”. He was so allergic to paying taxes that he ran right into to the avoidable RMD tax trap.

Ways to achieve this would be to actually enjoy and use some of the money that was saved. Like draw some out during 55 – 72!!

Wealth is NOT about perpetual accumulation. You might as well not have had it in the first place.

Money is such a mental trap that there could exist an outcome such as the one shown in Tawcan’s recent post.

To each his own I suppose. But to read the lengthy comments about the detriments of the RRSP was too much.

Just pay some taxes for Pete’s sake.

I read the Tawcan post too and agree with your comments. People have such an aversion to paying taxes that they’re not looking at the overall long term holistic picture. It’s okay to pay taxes, really. I would rather be paying a lot of taxes than not because it would mean that I had a high income.

The average person doesn’t understand that our tax brackets are progressive, never mind how different types of income have different tax treatments (earned/interest income, ineligible dividends, eligible dividends, capital gains, domestic versus foreign, etc.).

There are also estate planning considerations for RRSPs and RRIFs. I don’t think many people realize that deferring the conversion to RRIFs as late as possible and taking the minimum withdrawal has a potential risk of the estate having to pay taxes on a full disbursement upon death. You may have minimized RRIF withdrawal income taxes in life but your beneficiaries will receive less upon your death.

Grant, thats what my accountant tells me. Pay our taxes! He says he will never get to keep OAS. None of us paid into it like we did into CPP. Its designed for people of low income.

I’ve been going round and round on the Personal Finance Canada sub-reddit with an American who’s moaning about not being able to continue to contribute to his US Roth IRA while residing in Canada and finding out that TFSAs are “frowned upon” for US citizens. [BTW, I’m in the same boat as a dual citizen in Canada.] I told him that he had the choice/opportunity to max out contributions to his RRSP. I pointed out that there’s no tax-free money under either tax regime. His reply? “I’m not allowed to use a TFSA as an american. And is there even any point to doing post tax contributions to an RRSP? Will that suddenly make it behave like a ROTH and make the money tax free upon withdrawal. I think not. In which case there is no point doing post tax contributions to an RRSP.”

I just posted a link to this article as my final reply.

Good article and comments leading to a deeper understanding of investing taxation.

Note that in the consideration of average versus marginal tax rates, it is actually the average marginal tax rate that matters, both during a contribution to a registered account and withdrawal from it. A clearer label might be the “weighted average” tax rate for the transaction.

A $25K contribution is not unusual, even without borrowing. If Mr. Jones’ taxable income was $100K instead of $97K, his marginal tax rate would be 36% but his weighted average tax rate for a $25K RRSP contribution would be very close to 30.5% (since about 23K/25K would be in the 30.5% tax bracket).

I admit to being swayed by the article from the Tawcan site, and will reflect upon this further as I contemplate whether to contribute more money to my RSP beyond what my employer will match (in total that works out to about 50% of what my available RSP room is every year).

As an investor who intends to live in retirement from dividends my thoughts are that in retirement I’ll be paying higher tax by withdrawing the dividends from my RSP/RIF than if I were collecting them from my non-registered account.

I don’t see anything wrong with paying my fair share of tax now on my income, and on the dividends I collect on my way to retirement. I would really like the first few years of “early” retirement to be managed by only dividends, allowing us to delay CPP and OAS until at least 65, if not 70.

Also, with the investments in my non-registered account I can choose to sell occasionally and gift amounts to my children or charities with just capital gains implications. I can’t do that with my RSP, as withdrawals will be taxed as income.

Having said all that, I do think I will spend a little more time in Excel to run more stringent scenarios to better predict how things will turn out. I am definitely a proponent of paying one’s fair share of taxes. I avoid “cash deals” all the time for this very reason. I also think minimizing tax in retirement is a reasonable objective.

I am grateful to have access to various points of view on the subject so that I’m not constantly reading stuff that only confirms my beliefs. Thanks for providing the opportunity to consider the other side of the equation.

I would have to agree with the commenters that say the marginal rate is what is important here as I cannot alter the other sources of income.

As a further example, my average rate recently has been under 10% even though my marginal rate is 30%. I have reduced my average tax rate through a donation strategy but it does highlight the use of marginal rates. (Although I recognize this is not an “average” person strategy). But any further amounts I remove from the RRSP will attract tax at the 30% rate not my average rate. The average rate is just the RESULT of other decisions. The marginal is what I can base decisions on.

Another consideration is how profitable the investment turns out to be. Suppose you have $10,000 to put into either an RRSP or a TFSA. You are avoiding tax on $10,000 when it is put into the RRSP but you may be paying taxes on $50,000 when you take it out. That $40,000 increase is not taxed when removed from a TFSA. So it would seems that we should be putting our higher yielding investments into TFSA’s if we have both TFSA’s and RRSP’s. I am surprised that I have never seen a discussion of this idea.

If you do a search on ‘asset location’ you should find some info on this. You’ll find rules of thumb like putting expected high growth investments in your TFSA, and things like bonds in your RRSP. There’s also then the argument that segmenting your holdings like this actually changes your asset allocation percentages when considered from an after tax perspective. E.g. if you have a 60/40 portfolio and all your fixed income is in RRSPs and some of your equities are not, you may in effect be more like 70/30 or something. So some people will recommend having the same 60/40 holdings in each account type to counter this.

Hi Charlie,

I do see this kind of discussion quite frequently, but it’s misguided. If you have $10,000 to save, that’s either $10,000 in your TFSA or $15,000 in your RRSP (assuming a 1/3 marginal tax rate). Many rules of thumb about asset location become nonsense when you properly take into account RRSP tax refunds.

Good explanations from both Robb & Potato.

Thanks.

I am actually more interested in whether speculative investments are better placed in an RRSP or a non registered account.

For example, lets say someone invested $1,000 in Amazon 20 years ago ($12.49 July 01, 2001) and today its worth $297,520 ($3,719 July 01, 2021).

In Non registered account you would pay tax on only 50% gains as you sell stock but in an RRSP you simply pay tax on 100% of withdrawals from RRSP.

Even if we calculate that the $1,000 RRSP contribution generated an extra $200 Tax refund which we also used to purchase an additional 16 shares (now worth 16 x $3,719 = $59,504) it still seems like we are actually paying way more Taxes by putting speculative investments in RRSP?

What am I missing?

It goes without saying absolutely the best place for a speculative investment would be the TFSA but would next best place be RRSP or a non registered account?

Hi Jeremy, it actually doesn’t go without saying because you’re focusing on a winning speculative investment, which of course you can’t know the outcome in advance. If your speculative investment goes to zero (or near zero) in your RRSP or TFSA then you lose that contribution room forever. If held in a non-registered account, at least you’d get to claim a capital loss (or carry it forward indefinitely to help offset a future gain) along with the lessen learned that speculating doesn’t always end well.

Robb,

Good Point about speculative investments going to $0.00.

So how about less speculative investments such as Vanguard VXF…basically an index of global investments about 50% US and 50% International (no Canadian stocks).

since Aug 1, 2014 $22.67 – 7/1/21 $49.60 it has doubled in 7 yrs = annual return of 10%.

But an average 6% per year over 40 yrs = 10x increase in value so investing $10,000 gets you $100,000 and you would pay tax on $45,000 (50% x $90,000) in a non registered account.

Or in RRSP invest $10,000 + $5,000 Tax refund (personally I think 50% refund is higher than most people enjoy) = $150,000 in 40 years and you will be taxed on the full $150k.

If we say 30% Tax in retirement the RRSP wins

Non Registered = $10k + $45k + 70% x $45k = $86.5k

RRSP = 70% x $150k = $105k but

if the initial refund was only $2,500

$125k x 70% = $87,500

Wow! That’s only $1k better than a non-registered account and in my example it would seem that if you get anything less than a 25% refund for your RRSP contribution you might have been bettered to go non-registered?

Again, what am I missing??

I’ve blown through these made up examples and the math pretty quick so apologies for any math errors & same if I’m just missing something obvious.

Thanks for the discussion Robb.

I agree with you Robb. I believe that nobody should be using retirement investments like RRSPs for speculative investments. If you can afford to lose your retirement savings, you probably do not need an RRSP.

There are a few other important arguments is favor of RRSP contributions over TFSA contributions:

1. The money is much more locked in than in a TFSA, so you will likely hold on to the money until you retire. You will not take money out of your RRSP to buy a car!

2. The limit on TFSA contributions is too low to give you a comfortable retirement, if that is all you have besides CPP and OAS

3. Many employers contribute to RRSP savings; nobody contributes to TFSA savings

4. With a bit of planning you can avoid getting too far into OAS claw-back territory; but that will only happen after you build up a significant RRSP

One problem is also delaying RRSP withdrawals too long and being at the mercy of minimum withdrawals. You could start earlier and max out your current bracket, or use RRSP money rather than start CPP early.

Robb, I appreciate your attempt to address the RRSP/TFSA/Non-Registered debate and what you wrote is certainly worthy of adding to the broader discussion on this topic. For fun you could add some fuel to the fire and add to the debate the discussion over dividend income versus capital gains (held in non-registered accounts) for retirees, as all these topics always seem to get inter-twined and discussed.

I’m planning to retire in 10 years, less if I want or more should I choose, and after 30ish years of investing, in one form or another, here’s what I’ve learned about RRSPs/TFSAs/etc…so many of the debates that break out over what is right or wrong are pointless, because the analysis is just so complex and unique to each individual. Instead, the best we can hope for is for people like you to layout the principals, factors, and considerations that go into assessing what may or may not be right under what circumstances.

Now if someone was to write a book with 40 case studies (still might not be enough) looking at different people and which investment vehicle is right for them and in which order should they utilize them, and how that is influenced by their income level, if they have a pension (DC/DB/None), are they an employee, self-employed, or own their own business, what is their relationship status pre and post retirement, and does their spouse work and if so is their income higher, lower, or the same, and where are they planning on retiring (if you work in QB/MB/NS [high tax provinces] and contribute to a RRSP and then retire in BC/AB, you are looking at a 5-7% tax difference on your RRSP withdrawals in retirement),and how CPP/OAS/GIS work with all of this, and do they want to roll their RRSP into a RRIF or do they plan to divest some of those funds and do they want to leave an estate, and on and on.

Not to mention another consideration that I suspect many of the people who read your blog and other finance blogs (as I think we are generally decent savers/investors) will have to deal with is the question of how long they’ve been investing and how large their portfolio is and how those assets are split up in the different investment vehicles.

For instance, at 18 I started DCAing into mutual funds in my RRSP, as that’s all there was. In my mid 20s, I started my career in the public sector. At around 30, I realized two things. One was, oh-oh, my DB pension indexed to inflation is going to put me close to the OAS claw-back range before I even touch my RRSP! I haven’t put a new penny in to my RRSP since. This was pre-TFSAs and yes I realize this is fortunate problem to have, but it is one that many in the public sector have to deal with. The second thing I realized was that my pension was the world’s biggest bond and secured by government, so accordingly I got much more aggressive with my risk profile and I’ve been 100% in equities ever since. Prior to that my results were okay, but ultimately I’ve benefited from 30 years in the market (invest early and often) and with several more years to go I’m going to get killed on taxes when it comes time to get my money out of my RRSP.

The reality is at 18, and throughout most of my 20s, the last thing I thought of was the financial consequences of contributing to my RRSP while in a tax bracket that will end up being a couple of rungs below where I’ll be when I start withdrawing from my RRSP. Oh well, next time around I won’t make that mistake again! Plus somebody has to pay for all of our government spending.

Hi Aaron, I was in the same boat as a young investor contributing to my RRSP (before TFSAs existed). And you’re absolutely right that we could look at 40+ case studies and come to different conclusions.

One thing I’ll point out for public sector employees is that many can access their unreduced pension at around age 55 and could certainly start making small RRSP withdrawals at that time as well to supplement their income. This approach would also allow you to defer CPP and even OAS to age 70, which would further deplete the RRSP before age 71.

Hi Robb,

There have been many people here and there suggesting deferring CPP and OAS and spending their RRSPs. Im going to suggest, for discussion, that is a slippery slope if you have an estate and heirs. By spending our RRSPs and not receiving government money from age 65 to age 71, we are denying our kids or heirs possibly badly needed inheritance.

I think I can do better receiving the CPP and OAS now, and saving my RRSP. However, you or someone like you could do the analysis.

Its easy at age 71. If I die, my estate would have lost approximately $20,000 pre tax per year. Thats $120,000. If my wife and I are killed in a car accident together at age 71, its $240,000 pretax. Im not sure any of us should be that focused on getting more CPP and OAS by deferring when the reality is our heirs will lose and most of our kids are doing worse than we did at that age. They need our help.

Two friends of ours recently died of sudden onset pancreatic cancer at age 67. One was a teacher who contributed a lifetime into a DB pension plan. Sadly about 40% lost now as his wife gets 60%. If she dies soon, its all gone. A DB pension downside is there is nothing for the estate. If you can, there is nothing wring with deferring RRSP withdrawls until age 71. After that time, its mandatory. Im going to use my OAS and CPP now to preserve the RRSPs as part of my estate.

I am interested to hear what anyone else or Robb thinks.

Hi Steve,

You said you were interested in what others think so I’ll chip in this. Like you, my thinking also puts significant emphasis on how much of my wife’s and my estates can be passed into the hands of our kids.

For both my wife and I, our largest available component of retirement funding is our RRSPs, which are a reasonably significant size. We also have TFSAs and taxable investment accounts to help us along.

The problem with RRSPs as a component of value in an estate is the income tax hit. Upon one’s death, and assuming no spousal transfer via election, the entire remaining value of one’s RRSP becomes fully taxable as income in the year of one’s death. Talk about pushing up one’s top marginal rate! Dying toward the end of one’s intended final year of working income, with a sizable RRSP that has not been drawn down at all, is the ultimate RRSP tax disaster. 50% of the prize can be gone in a puff of income tax. All of the money put aside, at what turn out to be lower marginal rates for so many years, can end up being taxed at the highest possible rate before your kids can get any of it.

Of course, the RRSP holdings of the first spouse to go can effectively be passed along, on a tax deferred basis, into the RRSP of the surviving spouse. But this can compound the predicament of getting the cash out of the RRSP at a desirably efficient tax rate. In my case, my wife’s RRSP is bigger than mine, so piling my balance on top of hers just increases the likelihood of eventually paying a higher income tax rate on the value. And she wouldn’t have me to help her draw down the cash via pension splitting. So when I think of maximizing the value flowing through to the kids (or even to me), I think a high priority needs to be placed on drawing down the RRSP steadily, at a reasonable average income tax rate, and without spending all of the cash. Just because the money is withdrawn from the RRSP, doesn’t mean it has to be spent immediately. Instead, a significant portion of the withdrawn cash needs to be placed in investments outside of the RRSP, so it can re-grow some of that value already taxed-away upon withdrawal.

In my case my wife, who is several years younger than I am, will likely continue earning an income while I am working on drawing down my RRSP/RRIF. But the key is to get the money out of the RRSP as tax-efficiently as possible, in whatever the time I have to work with amounts to. For me, the ability to defer the beginning of CPP/OAS until I am 70 will also assist me in bringing that money out of the RRSP more quickly and efficiently than if I began taking that additional income earlier.

If all goes well, I hope to make the RRSP tax gambit – that the withdrawals are at a lower tax rate than what was deferred on the contributions – pay off the way it is theoretically supposed to. But that is not a guarantee from the outset. It takes a withdrawal plan and a sufficiently long retirement.

Food for thought!

Hi James. Ive already done all that analysis. My wife and I already split about $65,000 in dividends and another $5,000 in interest income. So taking RRSPs now to the point of avoiding OAS clawback is going to be a marginal tax rate of about 30%. Our future tax might be 40 – 50% as estate tax, you are correct. But again, spending it now is gone forever. Tax savings on $240,000 would be about $40,000 now. But the fact is $80,000 in taxes now. Gone from being invested. Its not worth the risk to the estate if we die. The estate will be short $240,000 and unless you ensure the $160,000 RRSP after tax go to estate in some way, if not, your kids lose.

I still believe a ‘bird in the hand now is worth more than two in the bush later’. You die around age 71, the estate loses. So Im taking CPP and OAS now. The government wants you to die so you do not collect. Im not letting them off the hook so easily.

How and when is the average tax rate calculated? It’s a key concept here but not fully explained. (Or did I miss it?)

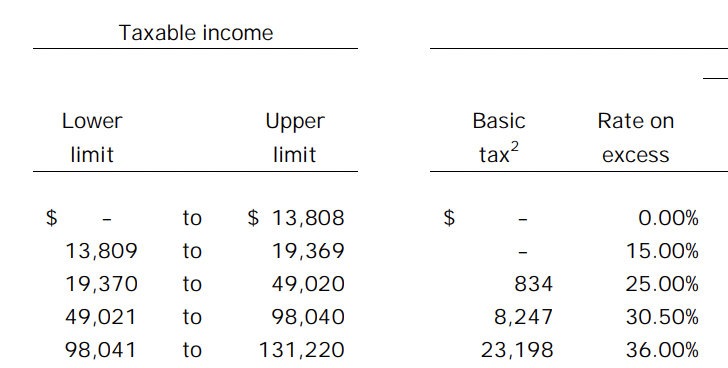

Hi Christine, we have a progressive tax system in Canada with higher rates of tax applied as your income goes up. The first $13,808 is essentially tax-free (the basic personal amount).

The next rung on the ladder (using Alberta’s provincial rates along with the federal rates) would be a tax of 15% on income earned between $13,809 and $19,369. The next rung is taxed at 25% on income earned between $19,370 and $49,020, and the next rung is taxed at 30.5% on income earned between $49,021 and $98,040.

So if your taxable income is $60,000 you don’t pay 30.5% tax on all of your income, but on the average of all the different rungs on the ladder.

In my example in the article Mr. Jones paid $11,596 in tax on his $60,000 of income, giving him an average tax rate of 19.33%.

EY.com has a great tax website to play around with different examples: https://www.eytaxcalculators.com/en/2021-personal-tax-calculator.html

Well Robb, your post certainly created some great discussion in the comments. One thing I didn’t see discussed is the federal and provincial Pension Income Amount tax credits. For those that don’t have a work pension (or other eligible pension income), having an RRSP pot that results in an annual RRIF income that fully utilizes these credits might be worth consideration when contemplating TFSAs, non-registered, or RRSPS as the best place for one’s money. I haven’t run the numbers, nor have I looked at the impact on GIS. Then, of course, where one has a spouse, there’s the added benefit of being able to split the RRIF income, potentially resulting in being taxed in a lower tax bracket. Also, both parties would benefit from the Pension Income Amount credits.

Hi Robb,

Would showing the math like this help clarify the situation?

Based on making either a $10,000 RRSP or $10,000 TFSA contribution in the same year and assuming a 20% investment growth for either investment over the time the investment is held.

RRSP contribution

$10,000 + $3,050 (tax refund) x 20% tax free growth of RRSP = $15,660 – $3,037 (taxes paid based on 19.33% aver. tax rate = $12,632.92

TFSA contribution

$10,000 + $0 (no tax refund) x 20% tax free growth of TFSA = $12,000

Based on the 19.33% average tax rate, the RRSP offers a $12,632.92/$12,000 = 5.27% advantage over the TFSA

The breakeven point between the RRSP and TFSA would be at a average tax of 23.3% (not sure what total income would be to put the taxpayer at that average tax rate?)

Once your average tax rate goes about 23.3% the advantage goes to the TFSA, but we must remember the TFSA limit is much lower than the RRSP limit based on a $97,000 income.

Hi Robb

Based on Conrad’s comment, I would be interested in an article discussing delaying CPP until 70 and funding the initial retirement years with only RRSP funds or convert the yearly withdrawal to RRIF funds for withdrawal for pension benefits. I believe someone could reduce the bulk of their RRSP account at a low average tax rate before age 70. For example, if the couple only wanted $60K / year but withdrew $90 – 120K combined per year (if it would maintain an average tax rate less than 20%) with the extra funds being re-invested into their TFSA and open investment account. Would this strategy minimize RRSP / RRIF taxes and reduce / avoid OAS clawbacks ?

FWIW, that is exactly my plan:

– delay CPP until 70 so as to get that 42% increase in benefits when CPP kicks in (at 70)

– fund the CPP “deficit” with increased RRSP withdrawals from 65 to 70

– convert a small amount of the RRSP to a RRIF at 65 so as to enjoy the $2,000 pension tax credit.

I do not have a DBP waiting for me, so “buying” increased CPP benefits helps to provide peace of mind w.r.t. longevity and market craziness.

YMMV, of course.

Hi Jim, I commented earlier that we are soending our kids inheritence by not taking CPP and OAS at age 65. If yiu maxed your CPP, the combined income with OAS is over $20,000 a year. Thats $120,000 pre tax. If you die then or even several years after and still havent reached age 78, your heirs end up with less. If you and your kids dont need the miney, no problem. Delay CPP and OAS.

Hi Steve

Fair enough. However, everyone’s situation is different.

This is me:

1) I’m only planning on deferring CPP, not OAS. OAS deferral does not provide as big a bang for the buck as CPP. The deferral works out to about $14,000/year, resulting in $70,000 over 5 years (in constant dollars) that needs to be financed from my RRSP.

2) Both of my parents lived long lives, so I’m likely to do likewise, barring being hit by a bus or something similar. As such, my concern is outliving my savings and/or getting whipsawed by the market, and increased CPP payments help to address those concerns.

3) My partner and I own our Vancouver house mortgage free. The house is worth a ridiculous amount of money due to the ludicrous appreciation in home prices that have occurred over the last several decades in Vancouver. So, our plan is to die with the last cheque bouncing and the 2 kids getting the house. IOW, the kids are actually better off, inheritance-wise, if partner and I die early. [I’ll add that we did help older kid buy a condo and will be doing something similar for younger kid].

As I said before, everyone’s situation is different and YMMV. This approach isn’t for everyone (like you basically say, if you need the money, you need the money), but I’m convinced it’s the right one for me.

Yeah, I’m with Jim on this one. Having an inheritance will be a bonus, just as it was for me. I’m glad my parents spent what they could, when they could, and I have to resentments now, nor did I have expectations about inheritance. In the end I received a modest amount of residual investments and some life insurance money. I’ll try to do the same for our children, but I’ll be making decumulation decisions, including CPP & OAS and RSP/RIF withdrawals based on our needs first and foremost.

Today we think we’ll have a primary residence, but my parents downsized, and then eventually sold and rented, so I don’t rule that out as an eventuality for my wife and I as well. It’s nice to think we’d live the rest of our lives in our eventual “forever home” but it doesn’t always work out that way.

Hi Jim,

We dont need the CPP or OAS. But im not taking any chance the government wins with my death early. Spending your RRSP is lost tax sheltered investing if it was invested. Nobody can predict the markets if it will have compounded growth for 10-30 years. Who knows. But spending it now, paying taxes is lost investment capital. Investing the proceeds is not tax sheltered either. I dont want more dividend income. It keeps pushing up my marginal rate closer to clawback. Im selling non reg investments for capital gains deductions and keeping our income around $80,000 each to avoid claw back. If we decide to splurge and cruise the world, buy a Mercedes, we will draw RRSP and pay 35-45% taxes. In all likelihood, we will live frugally like our parents, and not be spend thrifts. We are lucky markets went up. They could go other way. One day our kids will have an inheritance but they are not entitled to it now. They would simply blow it now.