For years I’ve been motivated to reach financial freedom by 45. I started a side hustle to accelerate our savings goals, and eventually turned that into a full-time entrepreneurial pursuit. Now that I’ve left my day job and can work on my own terms, it feels like I can finally coast towards financial freedom.

I’ve never been a fan of the traditional FIRE movement – mostly because of the ‘retire early’ aspect of FIRE (plus the emphasis on extreme frugality). But the concept of Coast FIRE is something I can get behind.

Coast FIRE is when you have enough saved early in life that you can meet your retirement needs by simply leaving your portfolio alone to compound and grow. No more contributions needed. That means the flexibility to dial back work without the pressure of having to maintain a high savings rate. Work and earn enough to meet your spending needs while your investments do their thing.

This reminds me of the parable of the twins – a tale told by banks and financial advisors about the power of compounding.

One twin starts investing early, setting aside some amount every year from age 25 to 35 and then stops. The second twin doesn’t start until age 35, but then invests the same amount every year until age 65. Assuming an identical rate of return, who ends up with the larger portfolio? The first twin does, by far, thanks to compounding over a long period of time.

That got me thinking. I’ve saved a bunch of money already (by age 41). I left my 9-5 day job to do something I truly love. The nature of my work means I can take on as few or as many assignments and clients as I want. Is Coast FIRE for me?

My RRSP and TFSA are maxed out. My wife’s RRSP is maxed out and by next year she’ll have maxed out her unused TFSA room. We started investing excess business income in our corporate account last year. We expect this account to be worth close to $200,000 by the end of 2021. By then we expect to have a total of $900,000 invested across our various accounts.

On the income side, we pay ourselves dividends from our business. Once my wife has caught up on her unused TFSA room we can scale back the amount we draw from the business. We have a sizeable emergency fund saved in cash to easily cover 10-12 months of spending.

I shared in my recent net worth update that I plan to intentionally work less in the second half of this year. We also have big plans to re-create our cancelled 2020 trips (fingers crossed) in 2022.

So I decided to run some numbers. I wanted to see what our financial plan would look like if we no longer contributed to our corporate investing account, and only contributed the annual amount to each of our TFSAs*, plus the kids’ RESPs**. That’s $17,000 per year saved on the personal side of our budget instead of the $56,000 we saved in each of the last two years (catching up on unused room).

*Hey, I can’t stop filling up our TFSAs.

**Hey, I can’t turn down the 20% matching government grant.

I figured we could reduce our business revenue by 35% – 45% and still meet our business expenses and personal spending needs. Reducing revenue could be as simple as no longer taking freelance writing assignments, and/or limiting the number of new fee-only financial planning clients I take on in a year.

The result is a less hectic, more balanced lifestyle. I can still do what I enjoy doing – writing about personal finance and investing, and helping people with their financial goals and retirement plans. But thanks to our diligent savings and hard work over the past 10 years I can ease my foot off the gas pedal when it comes to earning and saving more money.

At the heart of the Coast FIRE movement is the concept of ‘enough’. When John D. Rockefeller was asked how much money is enough, his answer was “just a little bit more.”

I’m pushing back against that idea. I don’t need to earn multi-six figures. I don’t need to build a corporate empire. I don’t need to save half my income for no good reason other than to grow the pile.

One of the reasons I left the hospitality industry early in my career was because I saw what happened to senior management and executives – they became burnt-out workaholics. That’s not for me.

So we’re going to allow ourselves to slow down. We’re going to let our sizeable and sensible investments ride for the next decade or more, contributing only modestly to our TFSAs along the way. We’re going to travel more (when we can), and enjoy more family and leisure time.

I have no intention of retiring early. I love helping people with their finances, both generally through the blog and also specifically through one-on-one financial planning. I feel like I have a lot more to contribute to the financial health of Canadians.

But the pressure is off now. I’m taking the Coast FIRE path from here on out.

I’ve read a lot of bad takes on RRSP contributions and tax rates over the years. One that stands out is the argument that you should avoid RRSP contributions entirely, and focus instead on investing in your TFSA and (gasp) your non-registered account. This idea tends to come from wealthy retired folks who are upset that their minimum mandatory RRIF withdrawals lead to higher taxes and potential OAS clawbacks. They also seem to forget about the tax deduction generated from their RRSP contributions and the tax-sheltered growth they enjoyed for many years leading up to retirement.

I’m hoping to dispel the notion of an RRSP disadvantage by reframing the way we think about RRSP contributions, RRIF withdrawals, and tax rates. Here’s what I’m thinking:

Most reasonable RRSP versus TFSA comparisons say that it’s best for high income earners to prioritize their RRSP contributions first, while lower income earners should prioritize their TFSA contributions first.

The advantage goes to the RRSP when you can contribute at a higher marginal tax rate and then withdraw at a lower marginal tax rate, while the advantage goes to the TFSA when you contribute at a lower rate and withdraw (tax free) at a higher rate.

If your tax rate in your contribution years is the same as in your withdrawal years then there’s no advantage to prioritizing either account. They’re mirror images of each other.

Related: The next tax bracket myth

This comparison focuses on marginal tax rates. But is this the correct way to frame the discussion?

Marginal Tax Rate vs. Average Tax Rate

Isn’t it fair to say that an RRSP contribution always gives the contributor a tax deduction based on their top marginal tax rate (assuming the deduction is claimed that year)?

But when you look at retirement withdrawals, shouldn’t we focus on the average tax rate and not the marginal tax rate?

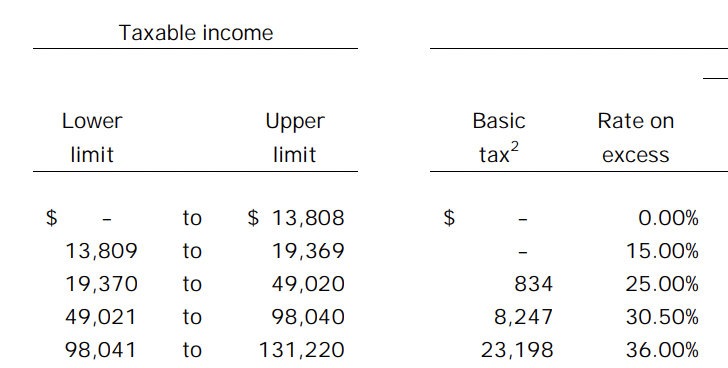

An example is Mr. Jones, an Alberta resident with a salary of $97,000 – giving him a marginal tax rate of 30.50% and an average tax rate of 23.59%

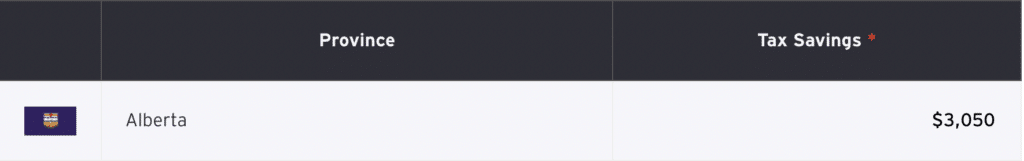

If Mr. Jones contributes $10,000 to his RRSP he will reduce his taxable income to $87,000 and get tax relief of $3,050 ($10,000 x 30.5%).

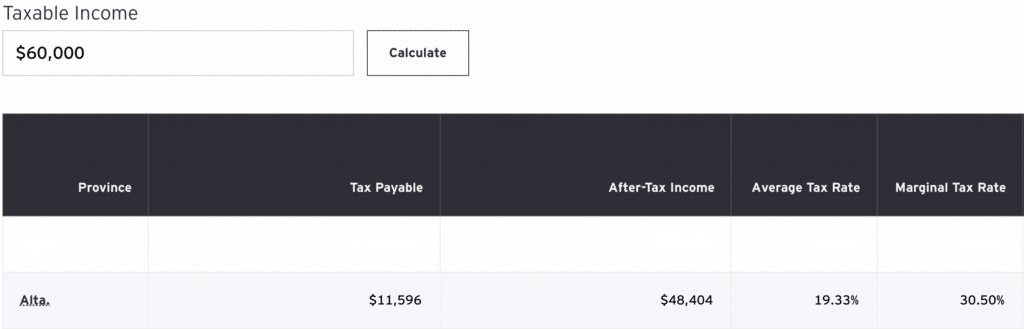

Fast forward to retirement, where Mr. Jones has taxable income of $60,000 from various income sources, including a defined benefit pension, CPP, OAS, and his $10,000 minimum mandatory RRIF withdrawal.

The range of income in each tax bracket can be quite broad. With $60,000 in taxable income, Mr. Jones is still at a 30.5% marginal tax rate, but his average tax rate is just 19.33%. That’s right, he pays just $11,596 in taxes for the year.

Conventional thinking about RRSPs and marginal tax rates would tell us that Mr. Jones should be indifferent about contributing to an RRSP in his working years because he’ll end up in the same marginal tax bracket in retirement.

But when we consider all of our retirement income sources, why do we treat the RRSP/RRIF withdrawals as the last dollars of income taken (at the top marginal rate) instead of, say, income from CPP or OAS or from a defined benefit pension? Why would Mr. Jones’ $10,000 RRIF withdrawal be taxed at 30.5% when it’s his average tax rate that matters?

Put another way, let’s say Mr. Jones asked his financial institution to withhold 30% tax on his $10,000 RRIF withdrawal. Wouldn’t he get a tax refund after filing his taxes revealed an average tax rate of 19.33% (assuming other income sources were taxed appropriately)?

What if we assume zero withholding taxes were taken from the defined benefit pension, CPP, OAS, and minimum RRIF withdrawal (of $10,000)? This taxpayer simply owes $11,596 at tax time (ignoring other deductions for simplicity). Why would we think the RRIF withdrawal is taxed at 30.5%? And, if we did, then which income stream is counted first and gets the basic personal amount treatment (yay, my CPP and OAS are tax-free!)?

The point is, all of your income streams converge into one pile of income and they’re taxed at your average tax rate.

Finally, I get that RRSP/RRIF withdrawals are often subjective – as in you can choose when and how much to take prior to RRIF conversion. You can also take more than the minimum from your RRIF, in which case your marginal tax rate may come into play when considering additional withdrawals.

But a lot of the pushback against contributing to your RRSP in the first place seems to come from high income retirees who argue that the minimum RRIF withdrawals are causing high tax rates and OAS clawbacks. So it seems like they’re not taking any more than the mandatory minimum – which makes the RRIF withdrawal a fixed amount similar to CPP, OAS, and the defined benefit pension.

Final Thoughts

I get there is a lot of nuance to this discussion, but my basic argument boils down to this:

It’s helpful to think about your RRSP contribution as always receiving a tax deduction at your top marginal rate, and to think about your RRSP/RRIF withdrawals as being taxed at your average tax rate (especially if you’re just taking minimum RRIF withdrawals). This strengthens the advantage of contributing to your RRSP and hopefully dispels any bad notions about avoiding RRSPs due to tax implications.

PS – this doesn’t even touch on the other RRSP advantages such as qualifying for additional Canada Child Benefit for parents with young children by lowering their net family income, or the ability for retirees to split RRIF withdrawal income after age 65 to save on taxes.

Bottom line: While there are situations when contributing to an RRSP is not a good idea (such as for low income earners who may qualify for GIS), most Canadians should be taking advantage of their RRSP contribution room for immediate tax relief, long-term tax-sheltered growth, and flexible retirement withdrawals at their average tax rate.

Do-it-yourself investors face a number of behavioural hurdles when it comes to building an investment portfolio.

We look to past performance to guide our future investing decisions – ignoring evidence that yesterday’s winners often become tomorrow’s losers.

We disregard decades of research that shows how low cost investing through passive index funds beats active stock picking strategies over the long-term.

We build needlessly complicated portfolios when simple, automatically rebalancing solutions exist.

We tend to panic when markets go down or sideways for a period of time, instead of accepting that volatility is the price of admission.

Put up your hand if you added a technology tilt to your portfolio after the NASDAQ returned more than 48% in 2020. Same goes for cryptocurrency or the latest meme stock.

Who increased their equity allocation after markets roared back to life last spring?

Which part of your portfolio did you tinker with to help hedge against higher inflation?

We can’t help ourselves.

I’m here to remind you to embrace the simplicity that comes from holding a single asset allocation ETF (or a robo advisor portfolio for those who don’t want to self-direct).

You’ll own 13,000 global stocks and 17,000 bonds inside of just one product. For that incredible simplicity and diversification investors pay as little as 0.20% MER.

Asset allocation ETFs help deal with a number of behavioural limitations. One, because they roll-up 4-7 underlying ETFs into one product, investors are less inclined to fuss over an asset class or region that is underperforming at the moment. Two, they automatically rebalance daily with new fund flows to maintain their target asset mix. That saves DIY investors from trying to exercise their own judgement and decision making.

Related: Why indexing doesn’t mean settling for average returns.

Some investors have a hard time embracing the simplicity of a single fund solution. I’ve seen portfolios that hold multiple asset allocation ETFs from different fund providers, which defeats the purpose of a single-ticket solution.

Maybe they’re trying to avoid putting all their eggs in one basket, but it’s helpful to remember that these products actually contain 4-7 underlying ETFs that represent thousands of stocks and bonds from around the world. It’s a big basket!

I get it. Investing doesn’t seem like it should be this easy. But it can be. Open a brokerage account, open the appropriate account types, fund the account(s), and purchase a single, risk appropriate asset allocation ETF. Then do nothing.

Your future self will thank you for generating the most reliable investment outcome. Heck, your current self will thank you for saving time and stress over managing your portfolio. Win-win.

This Week’s Recap:

We reached the halfway mark of 2021 and I shared my mid-year net worth update.

A reminder to check out my last weekend reading post where I shared some juicy new welcome bonuses from American Express. I’m well on my way to building back my Aeroplan balance.

From the archives: Why you should stop asking $3 questions and start asking $30,000 questions.

Thanks to Darcy Keith and Larry MacDonald for including my takes on leveraged investing in their Globe and Mail piece (subs):

“It reminds me of 2006-07 when the Smith Manoeuvre was getting a lot of uptake. Investors see strong market returns plus low interest rates and feel like they can dial up their risk with a leveraged loan,” Mr. Engen said. “Of course, the financial crisis put an end to that idea.

“Now a new batch of investors are looking at leveraged investing as a way to juice their already strong recent returns. I don’t think it’s a good idea. I’d ask anyone who is seriously considering a leveraged investment loan how they felt in March, 2020, when their non-leveraged investments were down 34 per cent and it looked like we were in for a prolonged bear market,” he said.

Promo of the Week:

DIY investors have two terrific options when it comes to saving money on trading commissions.

Wealthsimple Trade is Canada’s first and only zero-commission trading platform where investors can trade stocks and ETFs for free in an RRSP, TFSA, or non-registered account. Sign up for Wealthsimple Trade today and get a $10 cash bonus. I manage my RRSP and TFSA at Wealthsimple Trade.

For most robust investing needs, including for LIRAs, Margin, and Corporate accounts, Questrade is still the king of low-cost investing in Canada. You can purchase ETFs for free and trade stocks for as little as $4.95. Take your savings further with a registered account at Questrade.

Weekend Reading:

For those of you who aren’t interested in travel rewards, our friends at Credit Card Genius have compiled the best cash back credit card offers right now.

Great piece by A Wealth of Common Sense blogger Ben Carlson about how doing nothing is hard work.

Collaborative Fund’s Morgan Housel explains the casualties of perfection:

“Cash is an inefficient drag during bull markets and as valuable as oxygen during bear markets. Leverage is the most efficient way to maximize your balance sheet, and the easiest way to lose everything. Concentration is the best way to maximize returns, but diversification is the best way to increase the odds of owning a company capable of delivering returns. On and on, if you’re honest with yourself you’ll see that a little inefficiency is the ideal spot to be in.”

Read why young Canadians are dropping their do-nothing financial advisors salespeople for DIY investing.

Retiring from full-time work leaves a void. How will you fill it?

How is it okay that we’re meant to work a 9-5 for 40+ years and then retire? Maybe we’ve been bamboozled.

Jason Heath explains what you need to know if your retirement is riding on your rental property income.

Here’s Ben Carlson again with 16 unbelievable facts about the markets.

Professor Moshe Milevsky explains the difference between retirement and decumulation using an excellent example from Australia.

Some young clients fear missing out, while older ones may be sitting on unexpected gold mines. Here’s how advisors are rethinking their approaches with clients looking to get into, and out of, the housing market.

My Own Advisor Mark Seed looks at the role of an Executor when it comes to estate planning.

Finally, Millionaire Teacher Andrew Hallam explains how to become a digital nomad. Sounds tempting!

Have a great weekend, everyone!